Mexico City got its first subway line in 1969, shortly before Washington, DC and San Francisco opened their metros but long after Boston and New York City had gotten theirs. Over the past year and a half, I have visited Mexico City a couple of times and used the metro to get around each time. Here are some things I have noticed about the Metro CDMX system and the experience of riding it.

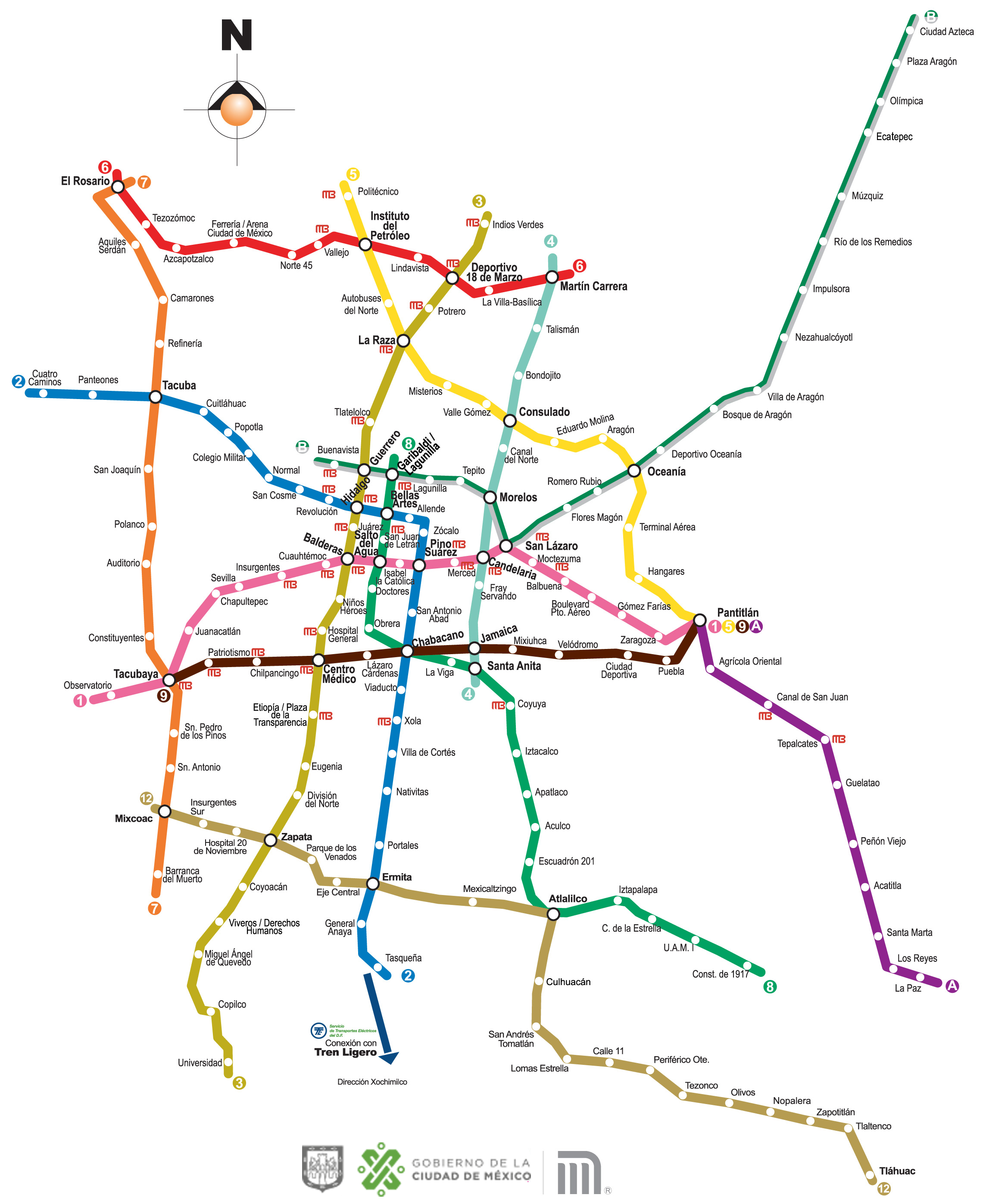

The most unique feature of Metro CDMX is that is is a decentralized network. Most metro systems start in the city center and radiate out into the suburbs, but Metro CDMX’s route map looks more like a net laid over the city. A decentralized network is more usable to more people, but it also means that you have to change trains to get almost anywhere.

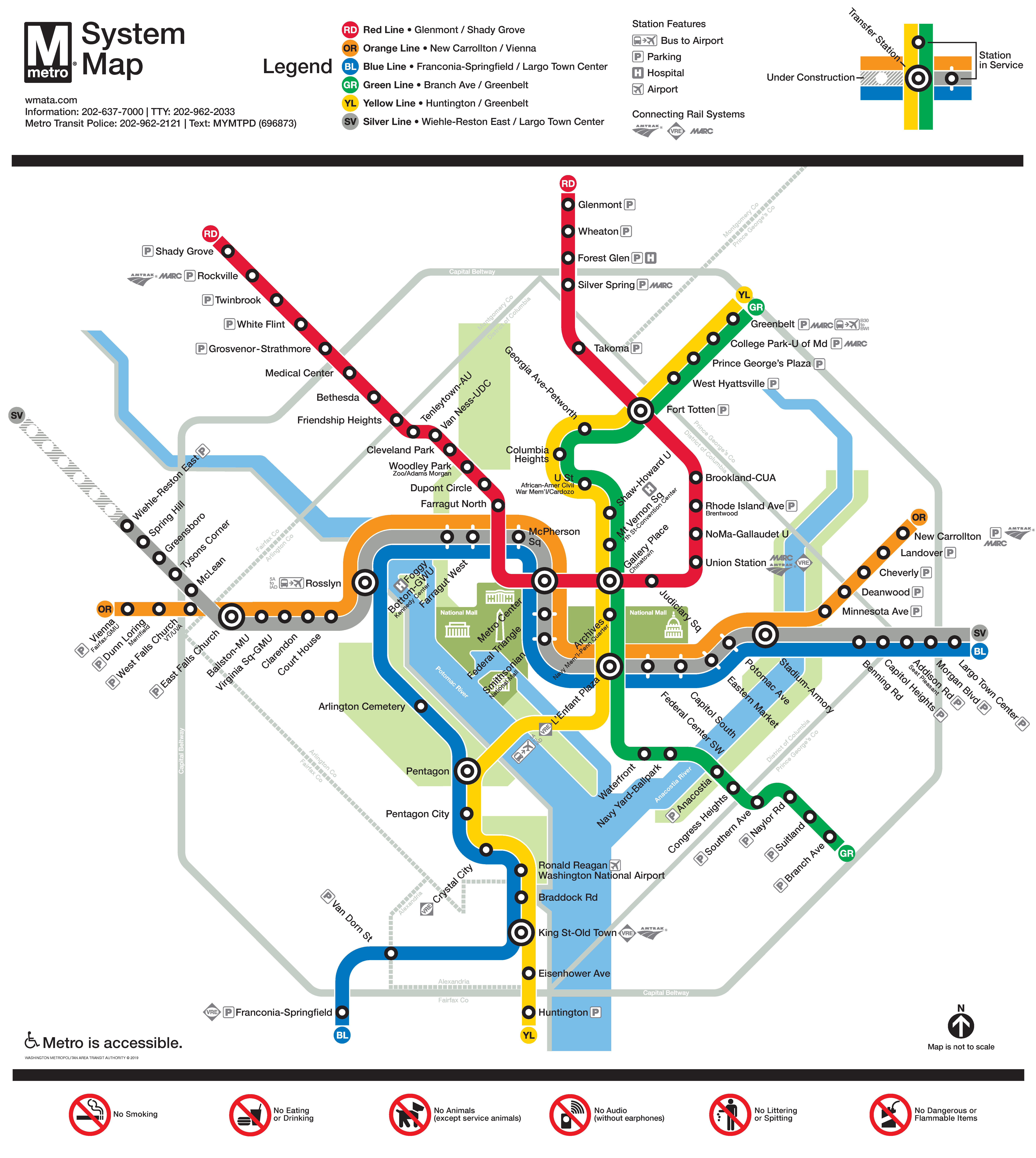

Route map of the Washington Metro. This is a centralized network, which makes it easy to go from the periphery to the center, or vice versa; but if you want to go from one part of the periphery to another, you will probably have to go through the center. (Source: https://www.wmata.com/schedules/maps/)

Route map of Metro CDMX. Since this is a decentralized network, you might not have to go all the way to the center if you want to go from one part of the periphery to another. (Source: https://www.metro.cdmx.gob.mx/la-red/mapa-de-la-red)

The rolling stock has rubber tires like buses, which run on metal tracks in the tunnels and stations. (There are also steel wheels running on conventional rails, but they are hidden behind the rubber tires.) The same technology is used in the Montreal metro, as well as at a smaller scale in various airport people-movers in the United States. I have heard it asserted that this type of metro is quieter than steel-wheeled trains, but I am dubious about that, because Metro CDMX trains do not seem any quieter than other metros I have ridden.

To ride on Metro CDMX, you can buy a paper ticket, or use an RF-ID smartcard with stored value. Either way, the price is the same: M$5 for a ride anywhere in the system. At 25¢ in US currency, this is amazingly cheap, probably the best value for public transport anywhere in the world.

Every metro station has a unique symbol associated with its name or the neighborhood it serves. The symbols appear on signage in stations and on the trains. Many of the stations are named after national heroes.

There is plenty of artwork in the stations, including murals, replica archeological artifacts, and displays of caricatures. The Zócalo station has dioramas of that part of the city over time.

When Pino Suarez station was under construction, this Aztec temple to Ehecatl, the wind god, was unearthed. It was restored and incorporated into the design of the station.

Metro trains in Mexico City tend not to get nearly as crowded as their counterparts in Delhi, even though Mexico City is the bigger city. The only time I got bodily pushed from behind into a crowded train car (a common occurrence in Delhi), that turned out just to have been a distraction created by pickpocketers. Ordinarily, when a train car is over-crowded, passengers just don’t get on the train. They line up on the platform and wait for the next train to come.

Some lines have vendors that sell things from train car to train car: snacks, books, CDs of folk music, anything that can be sold for M$10.

Metro CDMX farecards can be used on other systems as well, including buses and a single lightrail line connecting the metro to the canals at Xochimilco. The buses, like the metro, seemed to work well, but Tren Ligero (the lightrail) was overcrowded and slow when I rode on it.

Metrobus picking up passengers at a station on Avenida de los Insurgentes. (This is the same technology as the TransJakarta Busway.)