In 1941, as war clouds loomed over southeast Asia, a Chicago News correspondent by the name of George Weller flew from Cairo to Singapore on assignment. In Singapore, Weller reported on the British Empire’s ineffectual preparations for an attack that was sure to come from Imperial Japan. When the attack did come, it was not from the sea—as the British expected and were prepared for—but through the jungles of Malaya. Weller reported on the Japanese forces’ astonishingly effective campaign down the Malayan Peninsula and the subsequent doomed defense of Singapore. He was there until almost the very end, when the remaining British Empire forces in Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942. The following year, he published his firsthand account of the fall of Malaya and Singapore, the engrossing Singapore Is Silent.

![Japanese troops parading in Singapore after the fall of the city. [Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD]](http://www.willylogan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/JapaneseMarchSgpCity.jpg)

Japanese troops parading in Singapore after the fall of the city. [Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD.]

Something that I found particularly interesting in Singapore Is Silent was Weller’s account of his flight from Cairo to Singapore. The two cities are a little over 5,100 miles apart by the great-circle route, which runs mostly over the Indian Ocean and only crosses the southern part of peninsular India. A flight like this would be no big deal with a modern long-range airliner like a 787 (even thought it seems that there are currently no airlines offering direct service between Cairo and Singapore). But this was far beyond the range of the airliners of the day.

![A Short Sunderland Mk V in military (RAF) service. [Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD.]](http://www.willylogan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Short_Sunderland_Mk_V_ExCC.jpg)

A Short Sunderland Mk V in military (RAF) service. [Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD.]

In Singapore Is Silent, Chicagonews (as Weller calls himself in the narrative) flies to Singapore aboard a Short Sunderland operated by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC). The Sunderland was a flying boat, so it could only take off and land on water. The plane had a maximum range of 1,780 miles, which meant that it had to stop several times to refuel on its way to Singapore. BOAC routed its plane north of the great-circle route, sending it across northern India, where there were plenty of places to stop. Chicagonews’s route across India was this: Karachi (still a part of India at this point), Jaipur, Allahabad, “the narrow upper waters of the Ganges” (no city name specified), and Calcutta.

Karachi is on the coast and Allahabad and Calcutta are on the Ganges (Ganga) river system, but what about Jaipur? It is in arid Rajasthan, with no ocean or large river in sight.

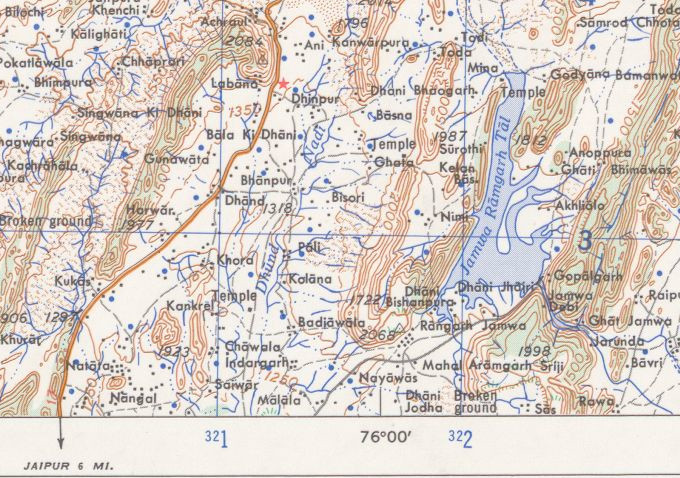

Chicagonews’s plane touches down on “the Rajah’s lake near Jaipur,” where a motor launch takes the passengers to shore. This was clearly one of the artificial lakes around Jaipur. Although I have not been able to find a source to tell me which one it was, I think that it was most likely Jamwa Ramgarh, an irrigation reservoir 15 miles northeast of the city that was built in 1901. With a long axis of about 4½ miles, the lake would have been long enough for the takeoff run of a big flying boat.

Jamwa Ramgarh Tal, as pictured on a 1963 US Army Map Service map. The lake has been dry since 2000. [Source: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection.]

The route crossing India by flying boat was a recent development. In the late thirties, Imperial Airways (BOAC’s predecessor) had taken its flying boats only as far as Karachi; for the crossing of India itself, passengers had transferred to landplanes and flown a route of Karachi–Jodhpur–Delhi–Allahabad–Calcutta. When Imperial Airways introduced flying boats for the crossing of India, the route was changed to Karachi–Rajsamand Lake (near Udaipur)–Gwalior–Allahabad–Calcutta.

The age of overseas travel by flying boats was brief. Long-distance routes like BOAC’s Cairo-Singapore were disrupted by Axis conquests during World War II. By the end of the war, land-based planes had become bigger, faster, and longer-ranged, so airliners could make overseas flights with fewer intermediate stops. For example, BOAC adopted the Boeing 377 in 1949, which had a range of 4,200 miles, more than twice the range of the Short Sunderland from just a decade earlier. The Boeing 707, which BOAC adopted in 1960, had a long enough range that it could fly all the way from Cairo to Singapore without making any stops at all in between.

The airport in Jaipur (now a strictly land-based airfield in Sanganer on the south side of the city) is no longer a stopover point for international flights. Long-range planes can simply bypass Jaipur on their way to bigger airports. Jaipur International Airport (JAI) does have direct flights to Dubai, but otherwise its traffic is domestic.