Sixty years ago today, on July 21, 1961, Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom became the second American to fly into space. Like Alan Shepard in May, Grissom flew a suborbital trajectory, because the Mercury-Redstone booster that he was riding on was not powerful enough to put his capsule, Liberty Bell 7, into orbit. Grissom took off from Cape Canaveral, Florida at 7:20 in the morning and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean fifteen minutes later.

When Grissom was waiting for the recovery helicopter to come pick him up, the explosive hatch on the side of the capsule blew off. Grissom dove into the ocean as the capsule filled with water, and he nearly drowned as water entered his spacesuit. The recovery helicopter was unable to lift the waterlogged capsule, and the winch operator had to cut the capsule loose. Liberty Bell 7 disappeared beneath the waves and sank to the ocean bottom, more than 15,000 feet below.

That could be the end of the story for Liberty Bell 7, but it isn’t. In 1999, a team led by underwater salvage expert Curt Newport, in the culmination of fourteen years of effort, found Gus Grissom’s capsule on the ocean floor. The team raised the capsule from the depths and whisked it off to the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center for conservation by the museum’s division Spaceworks. After conservation—and much media coverage—the Liberty Bell 7 went on a tour of science museums around the United States.

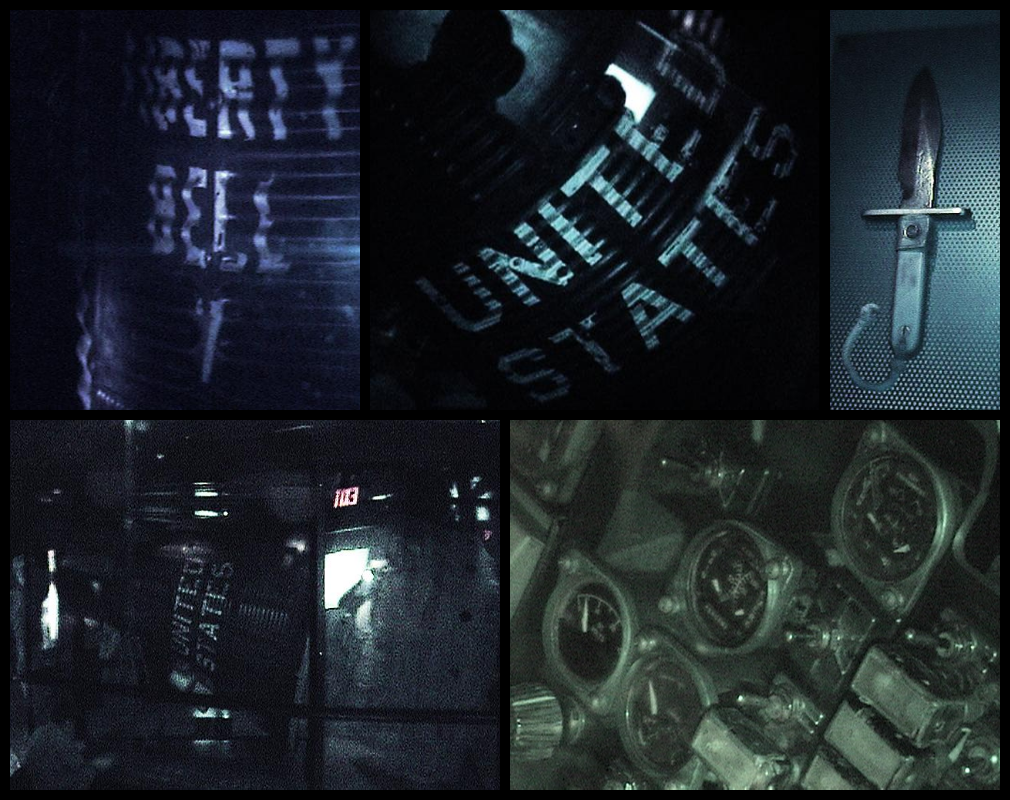

Some views of the Liberty Bell 7 on tour in Denver in early 2003. I was lucky enough to see it twice on its first tour.

The recovery of Liberty Bell 7 had cost millions of dollars, bankrolled by the Discovery Channel. Conservation cost another quarter-million. What was the point? Why go to the effort? There were a couple of reasons. One of them was that the recovery of Liberty Bell 7 presented a unique opportunity for a museum displaying American space artifacts. Because of an agreement between NASA and the Smithsonian Institution, all flown Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo spacecraft belong to the National Air and Space Museum. A few of them are displayed in Air and Space’s two museums in the Washington, DC area, and the rest are on loan to other museums around the country. But since Liberty Bell 7 had been lost at sea, Air and Space had no claim on the capsule. Just like for any shipwreck, Liberty Bell 7 belonged to whoever wanted to go to the effort of retrieving it.

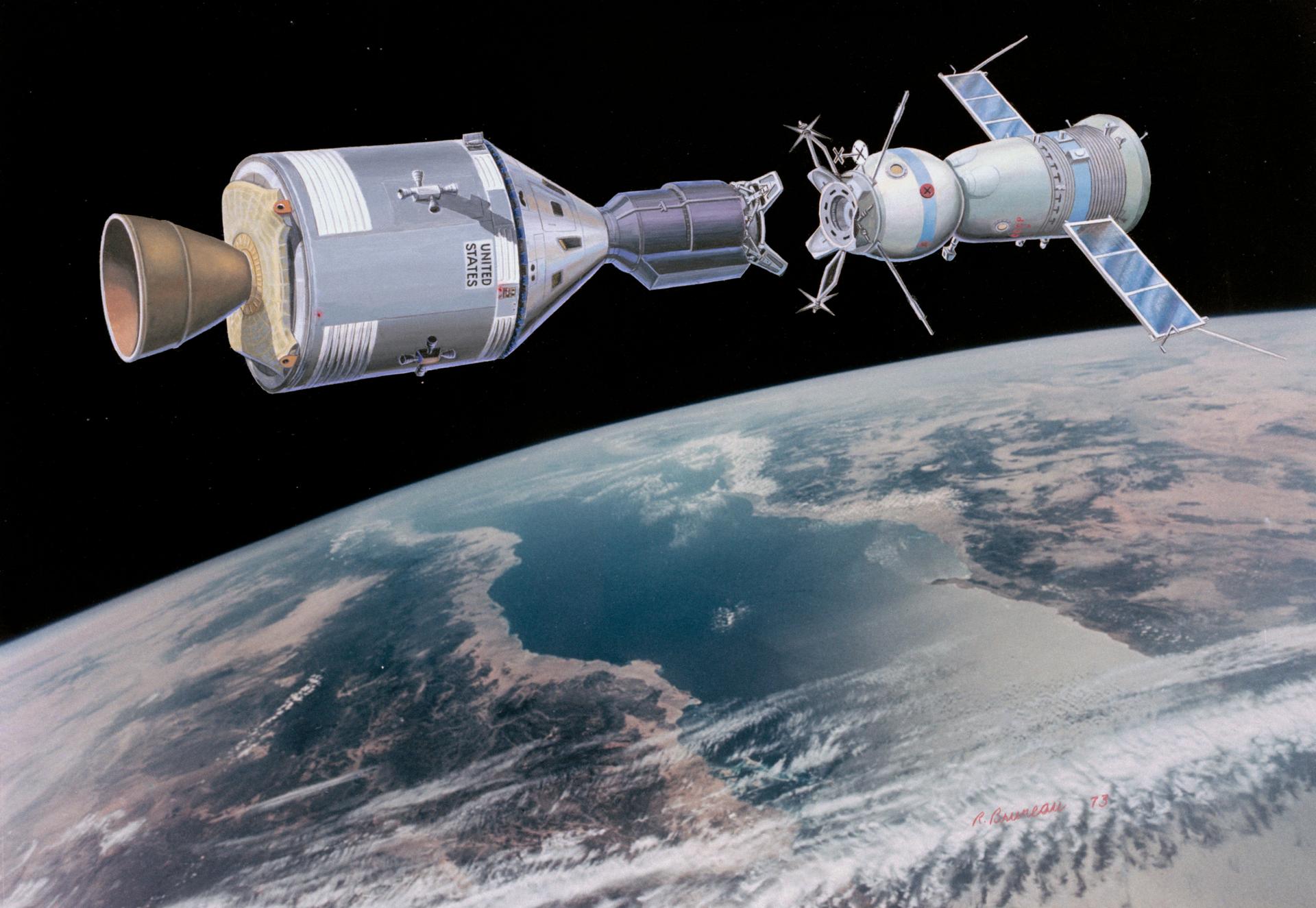

Another reason to recover Liberty Bell 7 was rarity. Between 1961 and 1975, American astronauts flew into space aboard a total of 31 Mercury, Apollo, and Gemini spacecraft. That might seem like a lot, but it isn’t when you consider how many cities and science and aerospace museums there are in the United States alone, not to mention the rest of the world. Every science museum would love to have a flown Mercury, Gemini, or Apollo capsule, but not every one can get one. Those that can’t have to make do with dressed-up boilerplates or replicas.

A third reason for going to such great lengths to recover Liberty Bell 7 has to do with how flight, and especially spaceflight, is understood as something magical in American culture. As Joseph Corn explains in The Winged Gospel, the early decades of the twentieth century were a period of widespread enthusiasm for flying in American culture. Americans believed that flight would usher in a technological utopia or millennium. Enthusiasm for flight declined after World War II when airplanes brought death and destruction rather than utopia, and when commercial flying became commonplace and banal.

Nevertheless, enthusiasm for aircraft, as well as spacecraft, persisted among some sub-cultures in the United States. To these people—generally pilot, aviation museum, and airshow types—aircraft made before a certain time (generally, World War II or earlier) were inherently historic, regardless of whether they had had anything to do with any great events. Museum restorationists obsessively preserved every last rivet and cotter pin of an aircraft while refurbishing it for display. Adventurers traveled to the ends of the earth (including the jungles of New Guinea and the ice cap of Greenland) to salvage World War II plane wrecks for restoration, sometimes even to flying condition.

If airplanes were magical and deserved this level of investment into their recovery, then spacecraft were doubly so, because they had flown higher and faster than planes, and were much rarer. Hence the recovery of Liberty Bell 7 at great expense. More recently, Amazon.com CEO and Wernher von Braun wannabe Jeff Bezos commissioned the recovery of the F-1 engines from the first stage of the Saturn V rocket that launched Apollo 11 to the moon, for much the same reasons as the recovery of Liberty Bell 7.

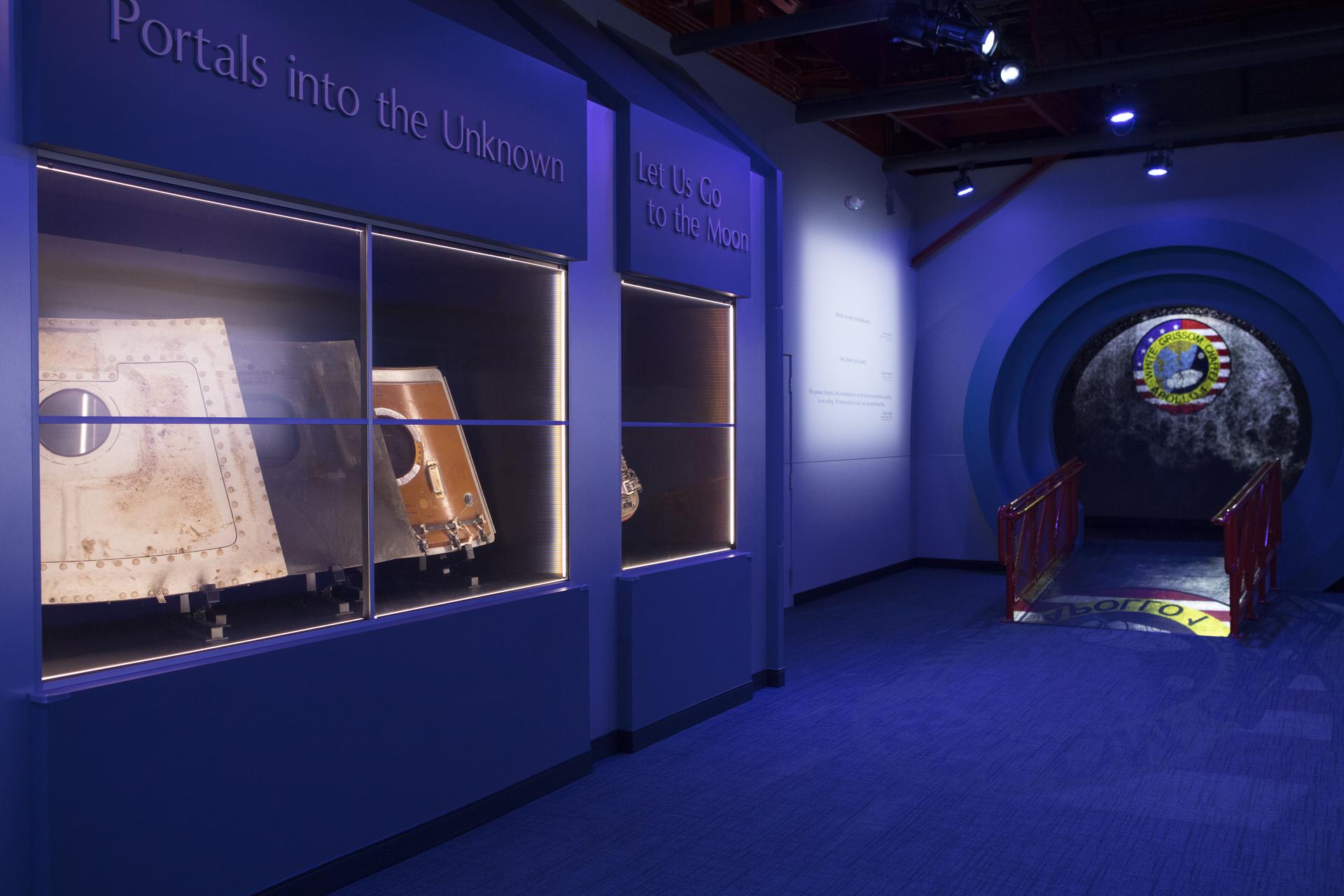

In a sad irony, while Liberty Bell 7 was recovered at great expense from the ocean depths for restoration and display, another of Gus Grissom’s spacecraft has never been put on display and maybe never will be. Grissom and two crewmates, Ed White and Roger Chaffee were scheduled to fly the AS-204 spacecraft, an Apollo Block I capsule, in early 1967. On January 27 of that year, during a simulation on the launch pad, a fire broke out in the capsule, killing Grissom, White, and Chaffee before the pad crew could get the spacecraft’s hatch open. The disaster prompted the redesign of the Apollo spacecraft into the safer Block II model. The Apollo 1 capsule (as AS-204 is retroactively known) remains in storage at NASA-Langley in Virginia.

The Apollo 1 capsule before the fire. (NASA photo)

The prime crew of Apollo 1 posing with a model of their capsule (L-R): Ed White, Gus Grissom, and Roger Chaffee. (NASA photo)

The original hatch of the AS-204 capsule was displayed at Kennedy Space Center in 2017, alongside an example of the redesigned and easier-to-open Apollo Block II hatch. This was the first time that any part of the capsule had been displayed publicly. (NASA photo)