“The commerce and general prosperity of both the Atlantic and Pacific shores of the American continent are so rapidly increasing as to call the attention of the civilized world to the great importance of Inter-Oceanic Railroads, extending without interruption from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

This is the opening line of “American Inter-Oceanic Railroads,” an article from the May 24, 1864 issue of the New York Daily Tribune. In 1864, during the American Civil War, the US government had recently commissioned the building of a transcontinental railroad to connect the Pacific coast states of California and Oregon to the states east of the Rocky Mountains.

The most immediate reason for building the US railroad was to connect the isolated, vulnerable, and valuable state of California, with its gold mines, to the rest of the country. But a longer-term reason, as the Tribune article appreciated, was to create a link between the Atlantic and the Pacific, thus enabling the United States to take part in the trade between the two great oceans. And the United States was not the only player in the game.

There was, in fact, one American interoceanic railroad already in operation by 1864: the Panama Railroad. When it opened in 1855, it crossed the Central American isthmus along a similar route to the future canal. The New York Daily Tribune article described four other railroad projects in some stage of planning that could compete with the United States’ transcontinental railroad; they were located in Nicaragua, the Andes Mountains between Chile and Argentina, Mexico, and British North America (Canada).

What became of these projects? Let’s take a look.

Canada

Construction of the first railway to link British Columbia with eastern Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway, began in 1881 and concluded in 1885. The Tribune article, written two decades earlier, only mentions the prospect of a trans-Canada railway in passing. The author of the article was more concerned about the political implications of railway projects in the republics of Spanish-speaking America.

The Andes

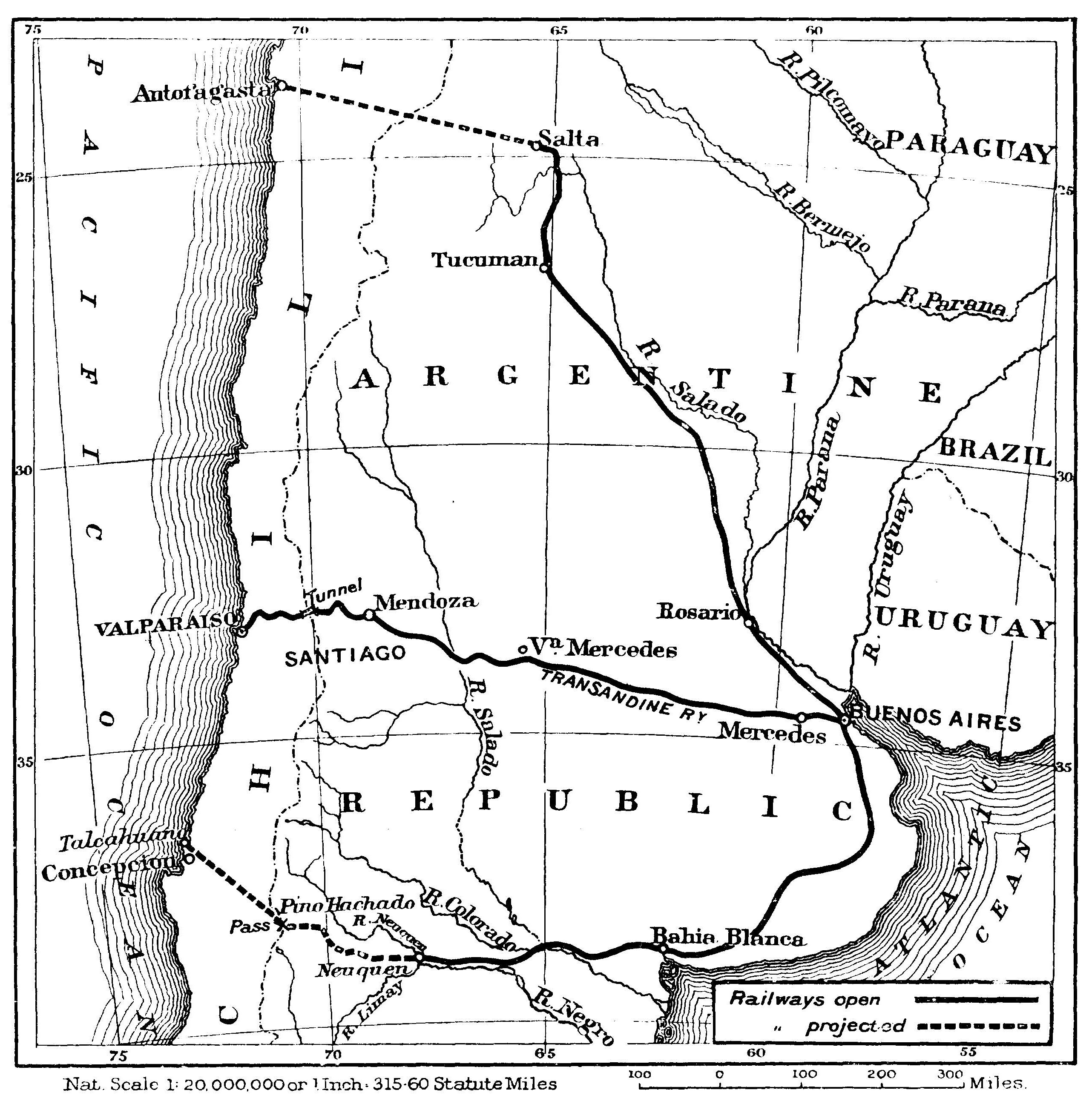

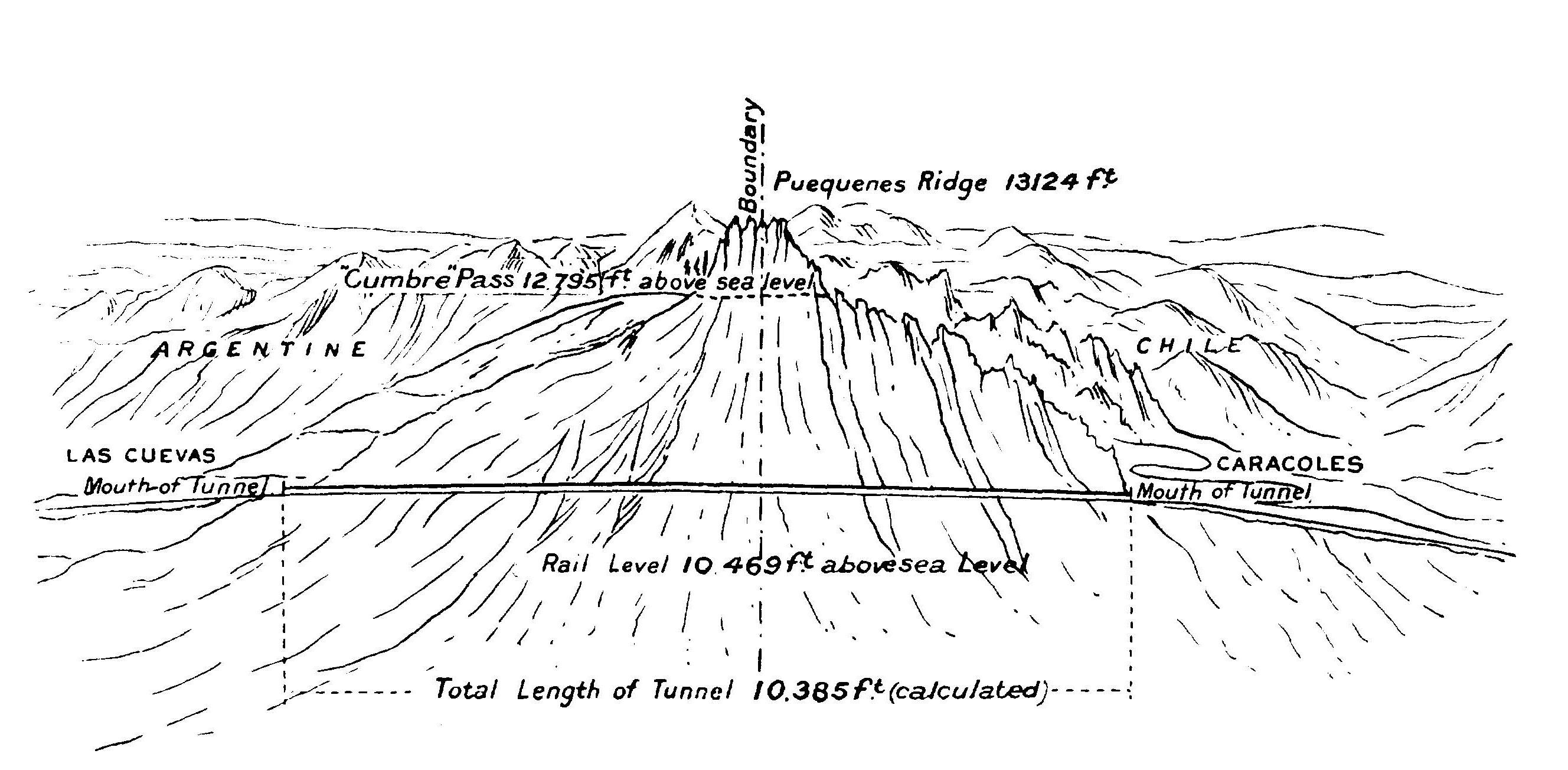

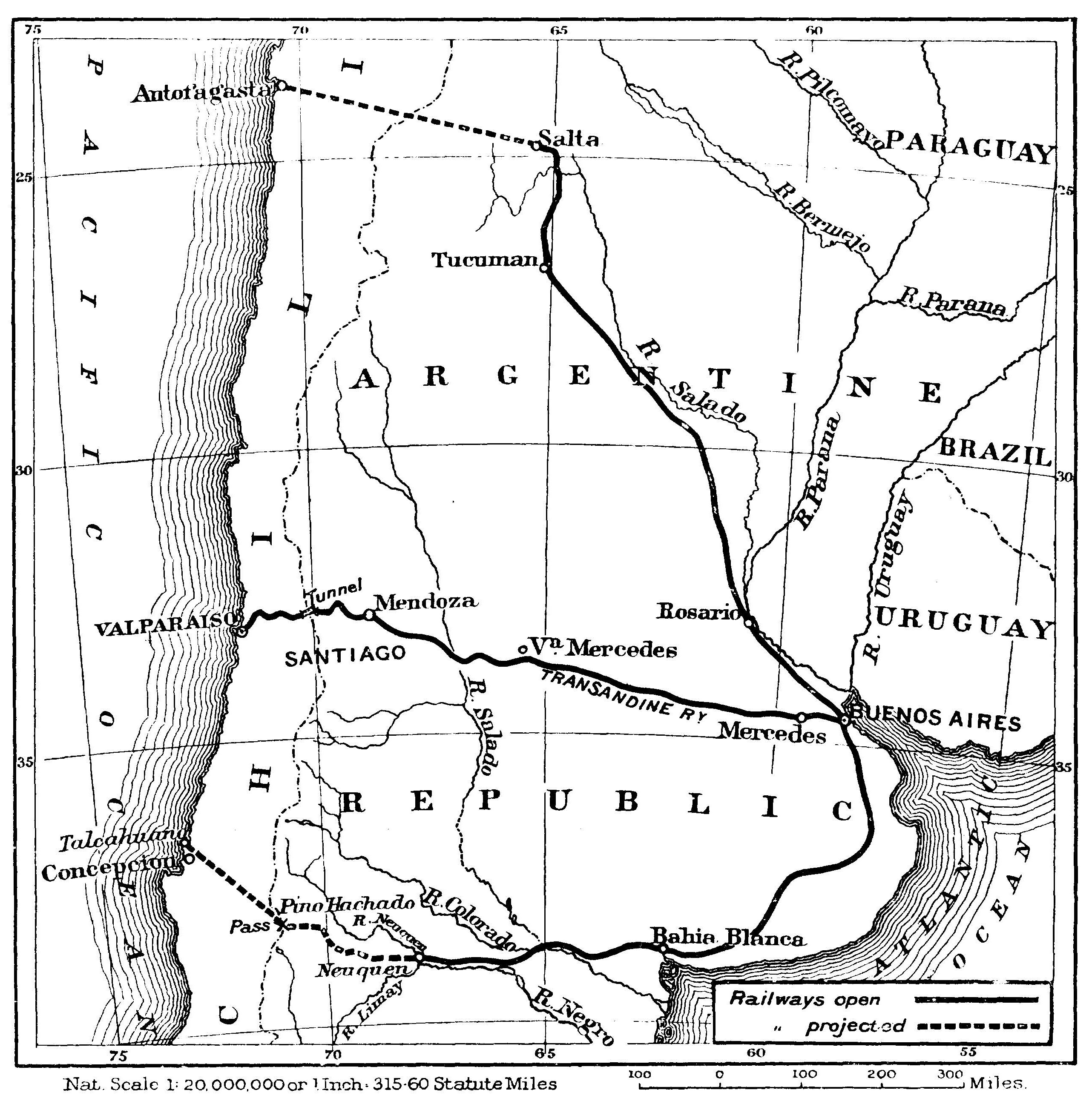

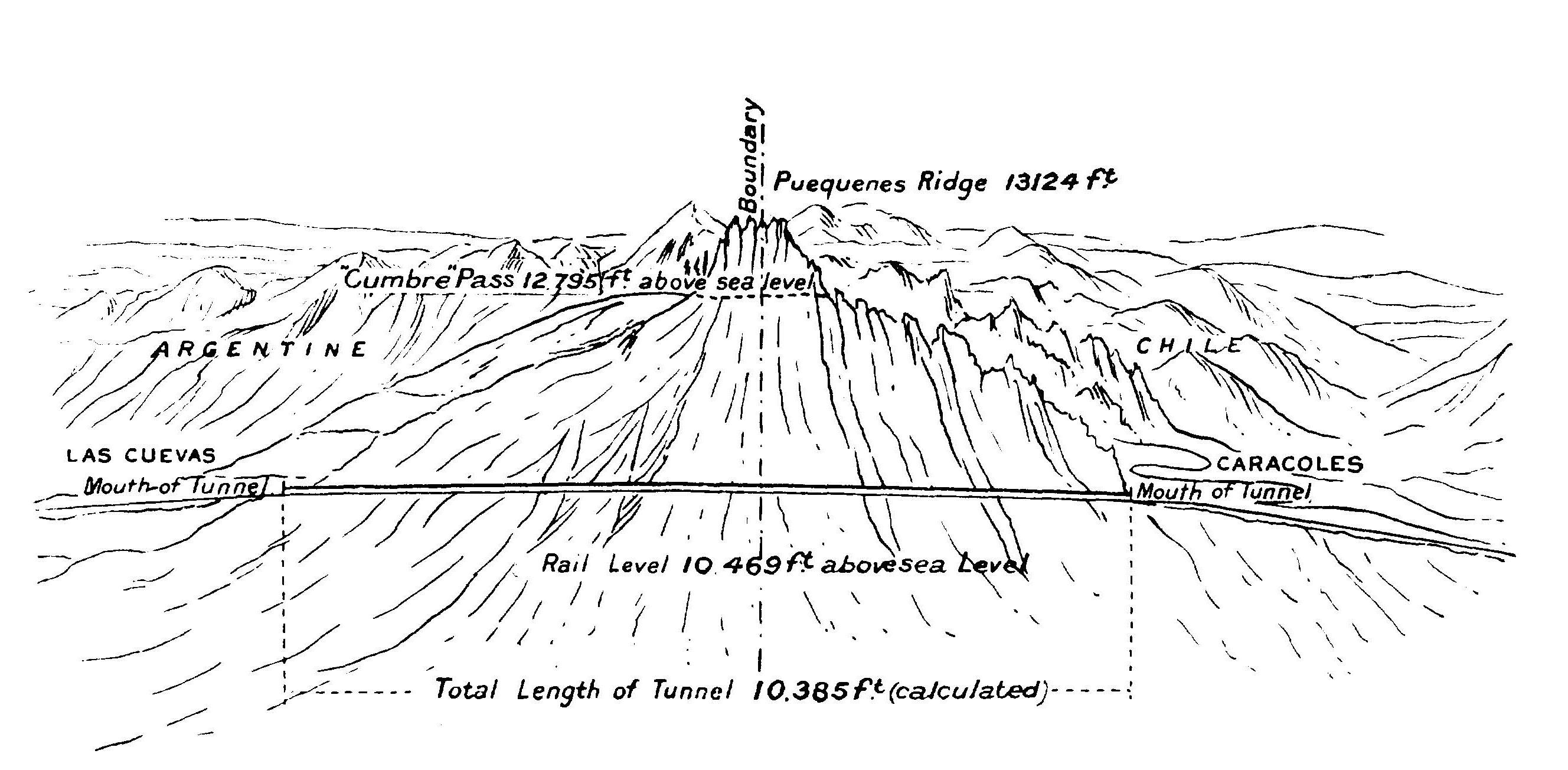

The Transandine Railway, the first railway across the great Andes Mountains of South America opened in 1910, almost fifty years after the New York Daily Tribune article mentioned the possibility of such a project. The rail route, which connected Buenos Aires, Argentina with Valparaíso, Chile, was actually a series of five separate rail lines, three Argentinian and two Chilean. The lines at lower elevation were built in broad gauge (5 ft 6 in), the same standard used in India, while the shorter lines near the summit of the Andes were built in the narrower meter gauge. The Chilean meter-gauge line crossed under the crest of the Andes at 10,969 feet in a three-kilometer tunnel, a remarkable engineering achievement. Although less impressive than the summit tunnel, the approaches on either side were actually harder to construct, especially on the Chilean side.

Map of the Transandine Railway between Buenos Aires and Valparaíso. (Source: Barclay, “The First Transandine Railway.”)

Diagram of the summit tunnel on the Transandine Railway. (Source: Barclay, “The First Transandine Railway.”)

The original Chile-Argentina Transandine Railway closed in 1984.

Nicaragua

The Tribune article describes in detail the Nicaragua Railroad, a transoceanic railway across the Central American republic. The article explains that the railway would pass alongside Lake Nicaragua and Lake Managua on its route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. A British company had contracted to build the railway. As stipulated by the contract, the company had to begin construction within two years of the signing of the contract, and complete construction before an additional seven years had elapsed. The company would receive large land concessions to aid in the construction, and the right to use forest resources from that land.

Although the Tribune characterized the Nicaragua Railroad as the “furthest advanced” among the projects in Spanish-speaking America, it is the only one that was never built. (A proposed canal across Nicaragua, cutting through Lake Nicaragua, also was never built.)

Mexico

In the eyes of the Tribune author, the most important interoceanic railroad project was a proposed line across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico. A foreign company had planned to make such a railway as early as 1842, but the Mexican government subsequently reneged on the agreement. According to an article in the Courrier des Etats Unis, Maximilian, the French puppet-emperor of Mexico, planned to recommence work on the railway. The Tribune saw this as a way for Maximilian to shore up support for his regime, thus threatening republicanism across the Americas:

“There is hardly any project by which Maximilian could better inaugurate the series of reforms which are to make the Mexicans forget the loss of their independence, and make a favorable impression, in behalf of the prospects of the Mexican Empire, upon the commercial classes of Europe, than the Tehuantepec Transit.”

The Mexican Liberals who opposed Emperor Maximilian found common cause with the Unionists of the United States, who were fighting to defeat the aristocratic, slaveholding Confederacy. American abolitionists celebrated the defeat of a French invasion force at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. (This is the origin of the Cinco de Mayo holiday.) After the defeat of the Confederacy, the Union gave military aid to the Mexican Liberals led by Benito Juárez.

Maximilian never did get to build his railway across Tehuantepec. Juárez defeated and executed him in 1867.

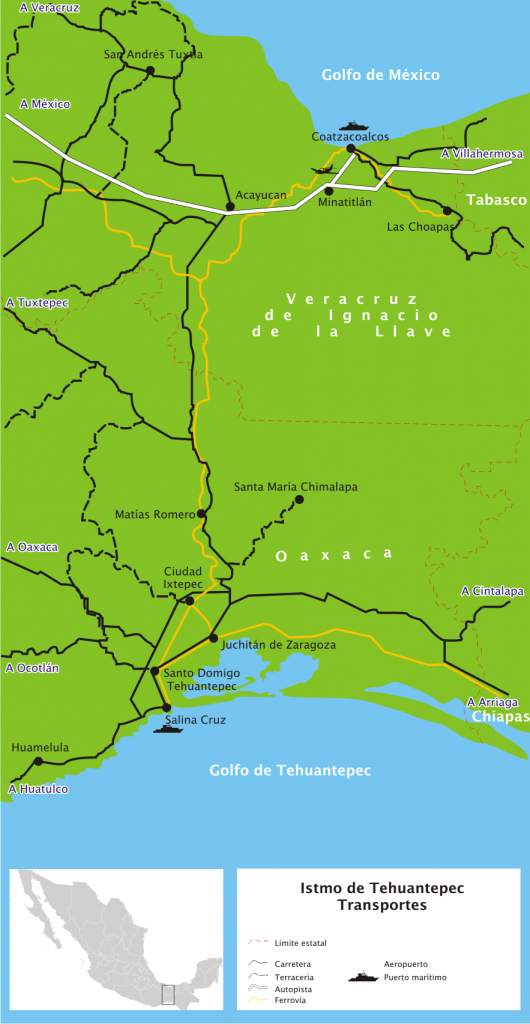

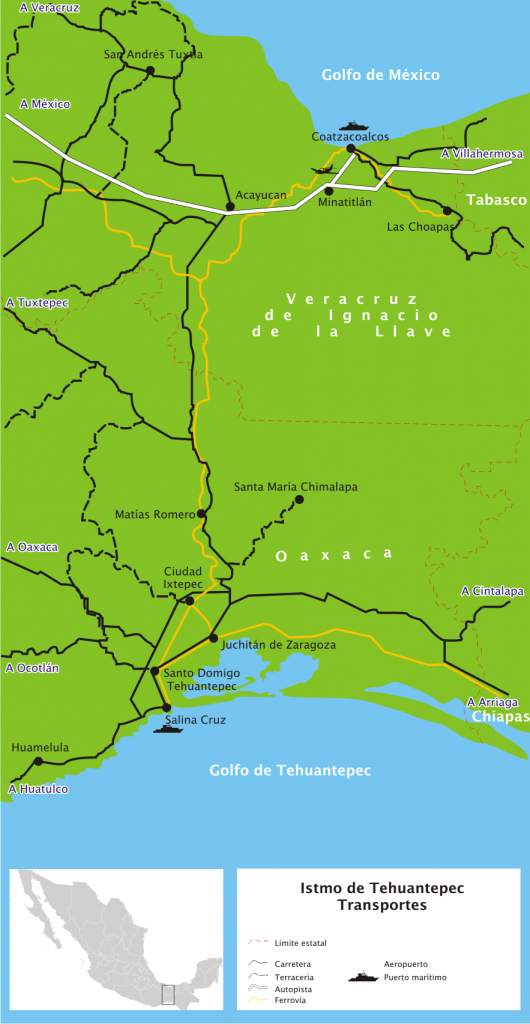

The Tehuantepec Railroad ended up being built a little later in Mexican history, during the Porfiriato (the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz). The railway was specifically built to serve as a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, not to carry local traffic. An early incarnation of the railway opened in 1894, but it consisted of different sections of track built at different times and to different standards, so it was not usable for interoceanic service. The Mexican government hired the contracting firm of S. Pearson and Son, Ltd. to overhaul the railway. From 1902 to 1906, Pearson replaced bridges, ties, and track; widened curves; and built new port facilities at Coatzalcoalcos, Veracruz (on the Gulf of Mexico) and Salina Cruz, Oaxaca (on the Pacific). The railway reopened in January 1907.

At first, interoceanic traffic boomed across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but in 1914 the Panama Canal opened and ate the Mexican railway’s lunch. Between 1914 and 1919, interoceanic tonnage across the Tehuantepec Railway dropped 99.7%.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is 125 miles across at its narrowest point. The highest point on the railway, Chivela Pass, is 735 feet above sea level, which is not very high. The total length of the railway is 192 miles. (Source: Wikimedia, PD-Self.)

References

Barclay, W.S. “The First Transandine Railway.” The Geographical Journal 36, no. 5 (1910): 553-62.

Glick, Edward B. “The Tehuantepec Railroad: Mexico’s White Elephant.” Pacific Historical Review 22, no. 4 (1953): 373-82.

Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies During the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.