“What can be said of a culture whose legacies to the future are mounds of hazardous materials and a poisoned water supply? Will America’s pyramids be pyramids of waste?”

–Giles Slade, Made to Break (2006)

I think that Giles Slade meant for this comment to be ironic, not taken literally. In the opening of Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America, Slade compares the landfills of modern America with the pyramids of ancient Egypt. As Slade would have it, it is an indication of our societal decadence that the great mounds that we raise are not tombs for our god-kings but final resting places for our junked PCs, outmoded cell phones, and plastic pop bottles.

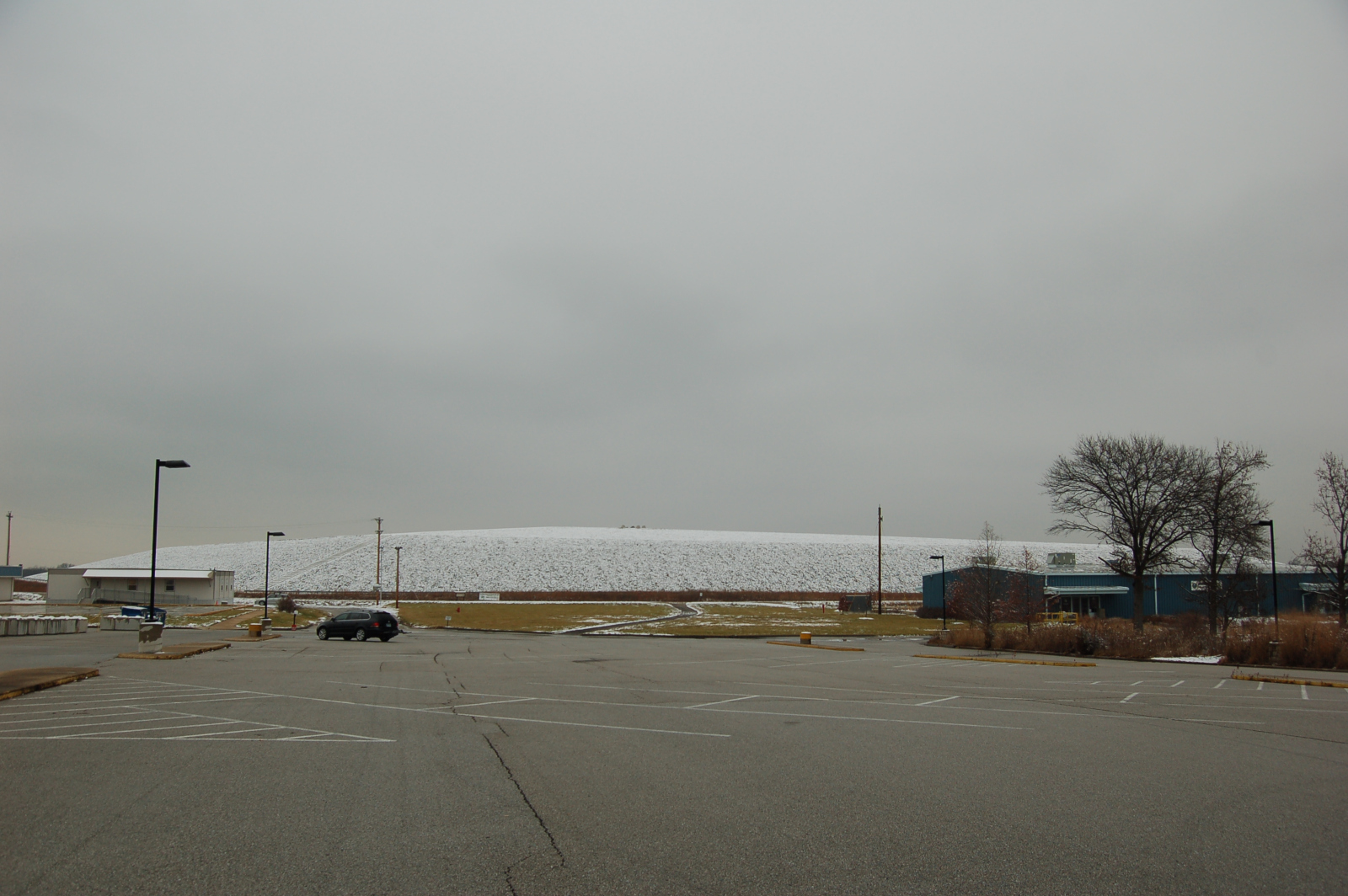

Of course, ordinary domestic landfills don’t really look like pyramids. Sometimes they have rectangular ground-plans; often they don’t. But there is at least one waste-containment mound that actually resembles a pyramid. It is in Missouri. And I’ve been there.

Weldon Spring Site is 30 miles west of St. Louis. During World War II, it was home to a munitions plant, which was converted to a uranium-processing facility in the Cold War. Like so many other Cold War industrial sites, Weldon Spring had plenty of radioactive and hazardous chemical waste lying around when it was abandoned in the 1960s. The Department of Energy took over the site twenty years later and began cleaning it up. All the untreatable chemical and radioactive waste from the site was entombed in an enormous mound. With its sloping sides and flat top, the mound looks a bit like a Mesoamerican pyramid, not so much an Egyptian one. (It is also a little reminiscent of the Cahokia Mounds nearby in Illinois, built by the Mississippian mound-builders.)

I should hope that some of modern America’s more inspiring monuments prove as durable as our pyramids of waste. At least what the Weldon Spring pyramid says about us is that we cared enough to clean up the mess we created (albeit twenty years late).