Sacramento is California’s sixth-largest city, but apart from being the state capital, it isn’t known for much. It lacks the mystique of San Francisco, the sex appeal of Los Angeles, and the prestige of San Diego. Far from being a center of information technology or mass culture, Sacramento is surrounded by miles and miles of irrigated farmland in the Central Valley. I have been visiting Sacramento my entire life, because one branch of my family has lived there since 1964. Apart from the state capitol complex, Sacramento always seemed a generic place to me.

I was a space nut growing up, and I was thus astonished when I learned just recently that Sacramento played a small but crucial role in the Apollo moon-landing program. Between 1962 and 1969, Douglas Aircraft Company tested upper stages of the Saturn rockets at a test range south of the city.

For the past three years, I have lived just two counties west of Sacramento, in Napa County. Once I learned about Sacramento’s link with the Apollo Program, I resolved to go to the old rocket-testing site to find out if there was anything left to see there. Thus I headed down to Sacramento one weekend for a bit of space-age technological tourism. Here is what I saw.

Douglas and the Saturn upper stages

The Douglas Aircraft Company test site was called Sacramento Test Operations, or SACTO for short. It was carved out of a larger facility owned by Aerojet, the rocket engine manufacturer. Technically, SACTO was located in Rancho Cordova, well outside of Sacramento proper. This was a precaution for safety, in case the rocket stages were to explode during testing (which happened a couple of times). The site was covered with mine tailings left over from the Gold Rush, and it wasn’t useful for agriculture or development—or really anything aside from testing rocket stages.

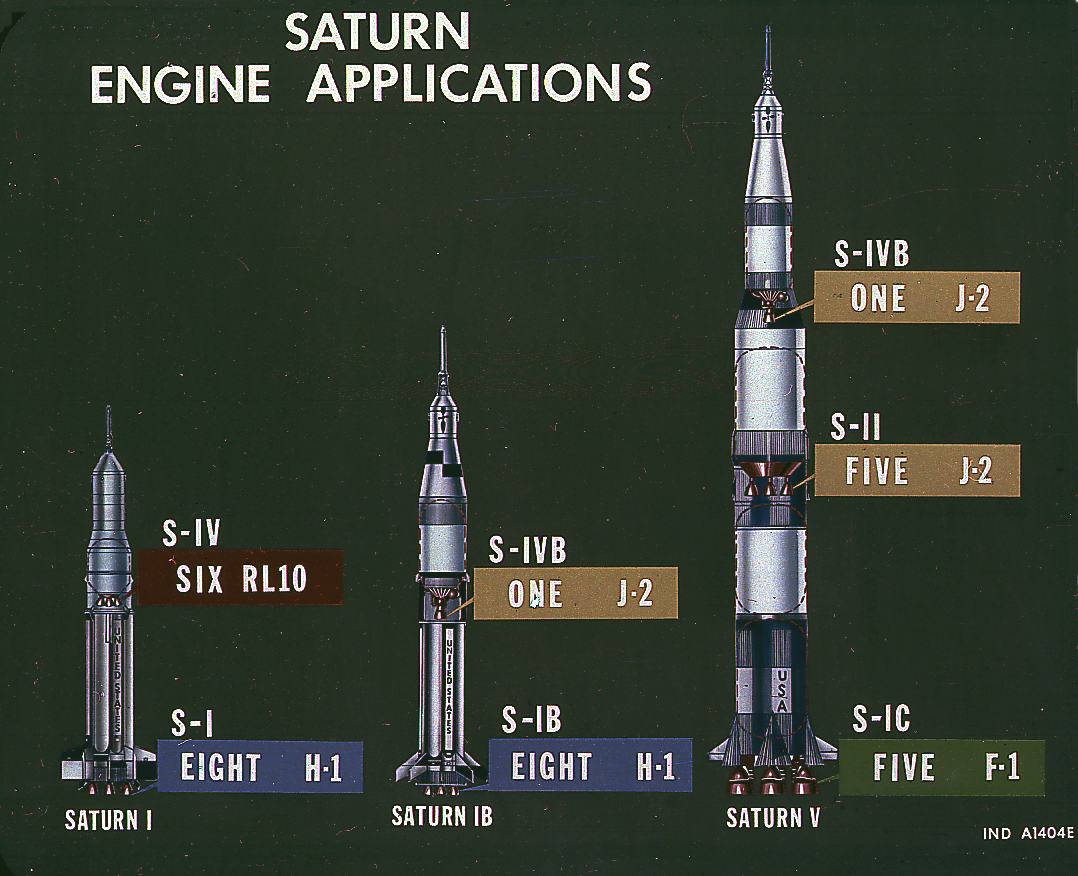

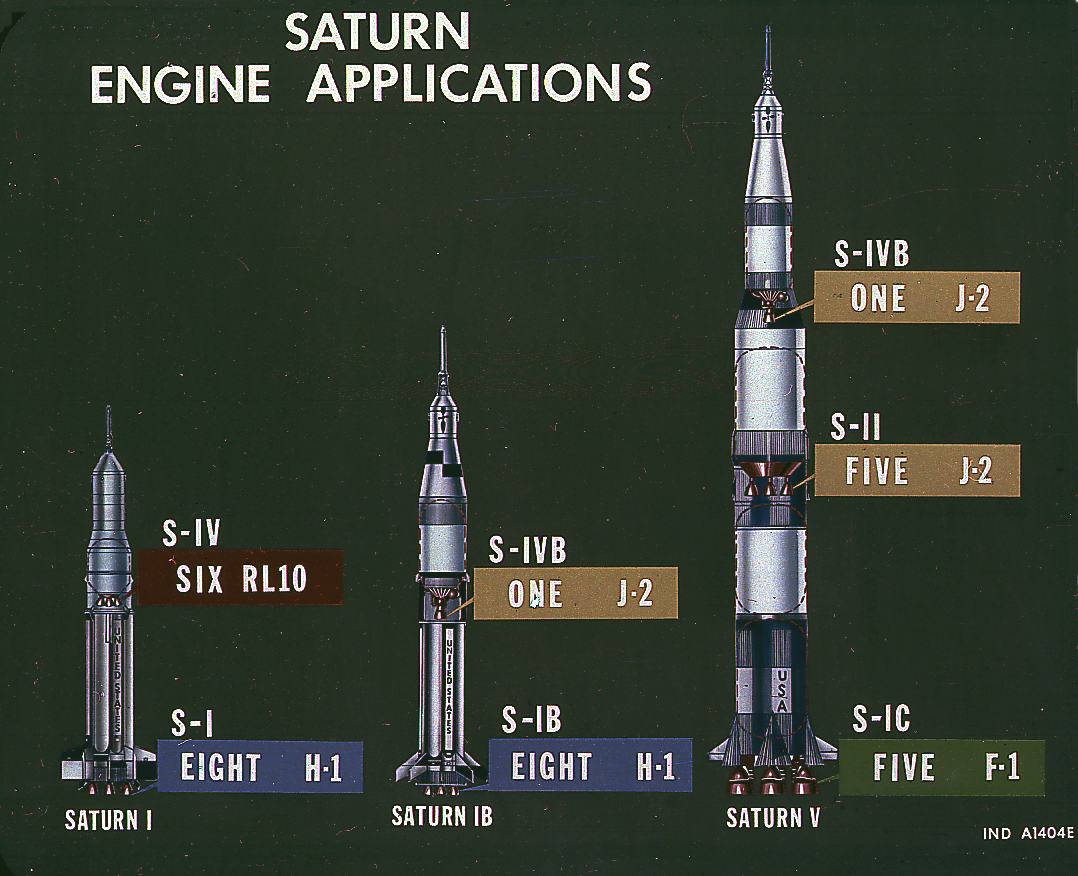

SACTO was originally constructed to static-test Thor missiles in the mid-fifties. In the early sixties, Douglas shifted to test Saturn upper stages there. The Saturns were some of the largest rockets ever flown, and they were developed in three phases:

- Saturn I: an R&D program to test clustering of engines and other concepts needed for large rockets.

- Saturn IB, originally “Uprated Saturn I”: a booster used for testing the Apollo spacecraft in Earth orbit.

- Saturn V: a very large booster used for launching crewed Apollo missions to the moon.

The Saturn rockets were developed under the direction of the Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The lower stages of the first Saturn rockets were built in-house at Marshall, while later stages were built by contractors.

Common-scale drawing of the three Saturn rockets: the Saturn I, Saturn IB, and Saturn V. All three rockets had upper stages built by Douglas and tested in Sacramento. (Source: NASA)

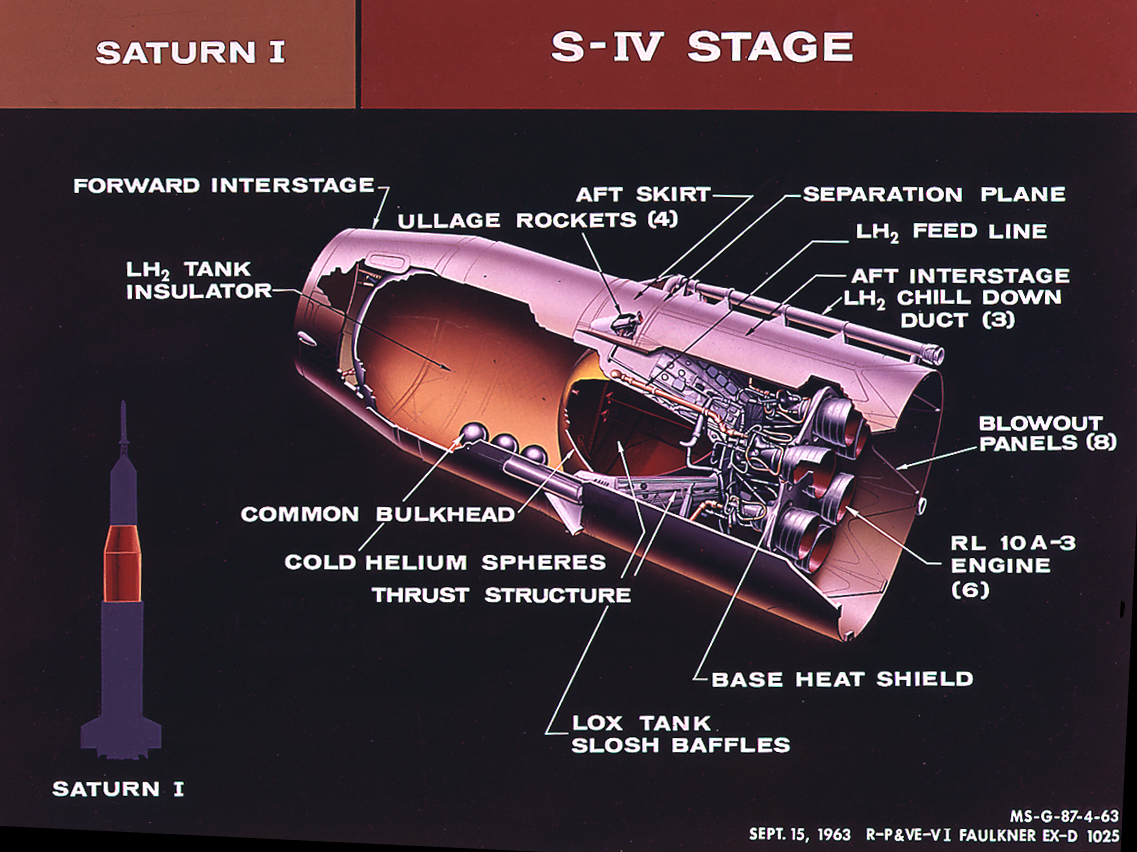

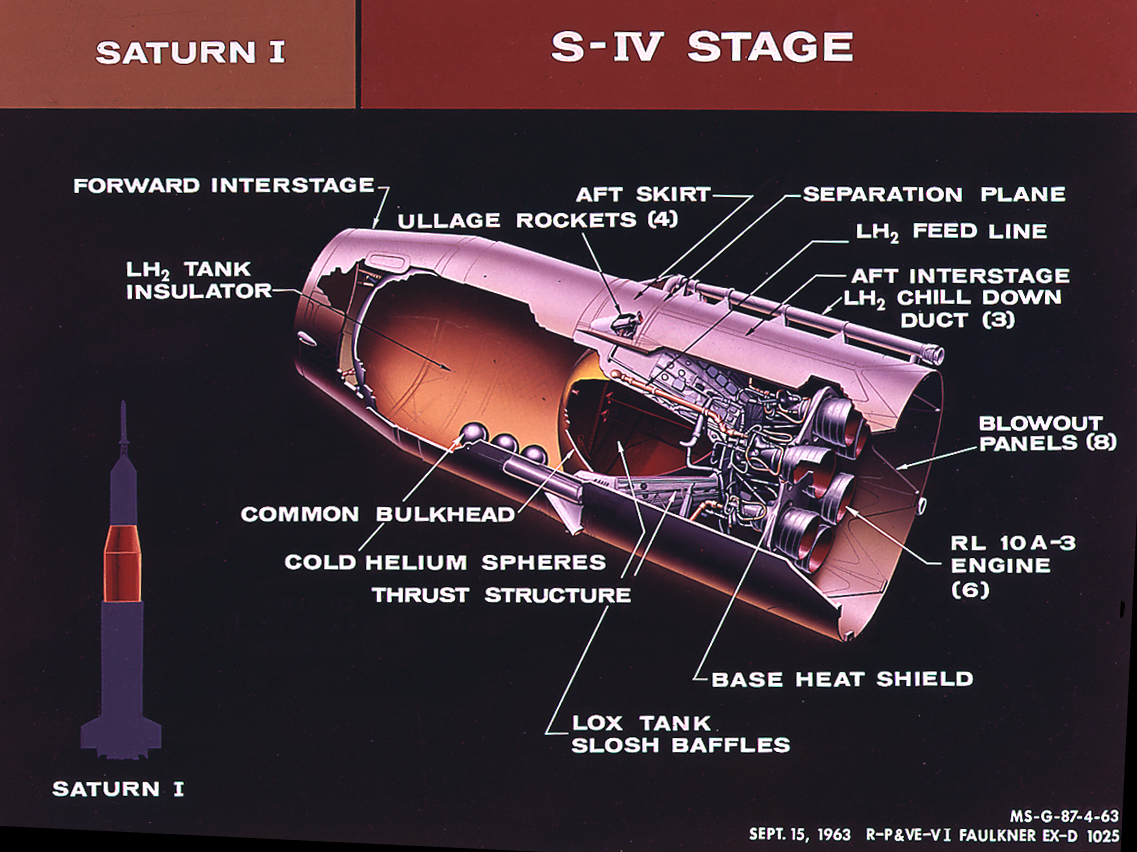

The Douglas Aircraft Company won the contract to build the upper stages for all three versions of the Saturn. The upper stage of the Saturn I was called the S-IV. It used liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen for propellants, which were considered to be high-tech at that time and required some special attention in the design process. The stage used six RL-10 engines for a total thrust of 90,000 lb.

One of the challenges faced in the design of the S-IV was insulation for the liquid hydrogen tank. Liquid hydrogen is extremely cold—cold enough to freeze air solid! It was imperative that the tank was insulated so that air did not freeze onto its outside surface. Douglas applied blocks of insulation to the inside of the tank. When searching for a material to use for the insulation, Douglas considered lightweight balsa wood, although this was eventually rejected because there was not adequate supply of balsa to line the tanks of all the rockets that were planned to be built. Instead, the Douglas upper stages used a type of fiberglass that mimicked the properties of balsa wood.

Cutaway drawing of the Saturn I S-IV stage. (Source: NASA)

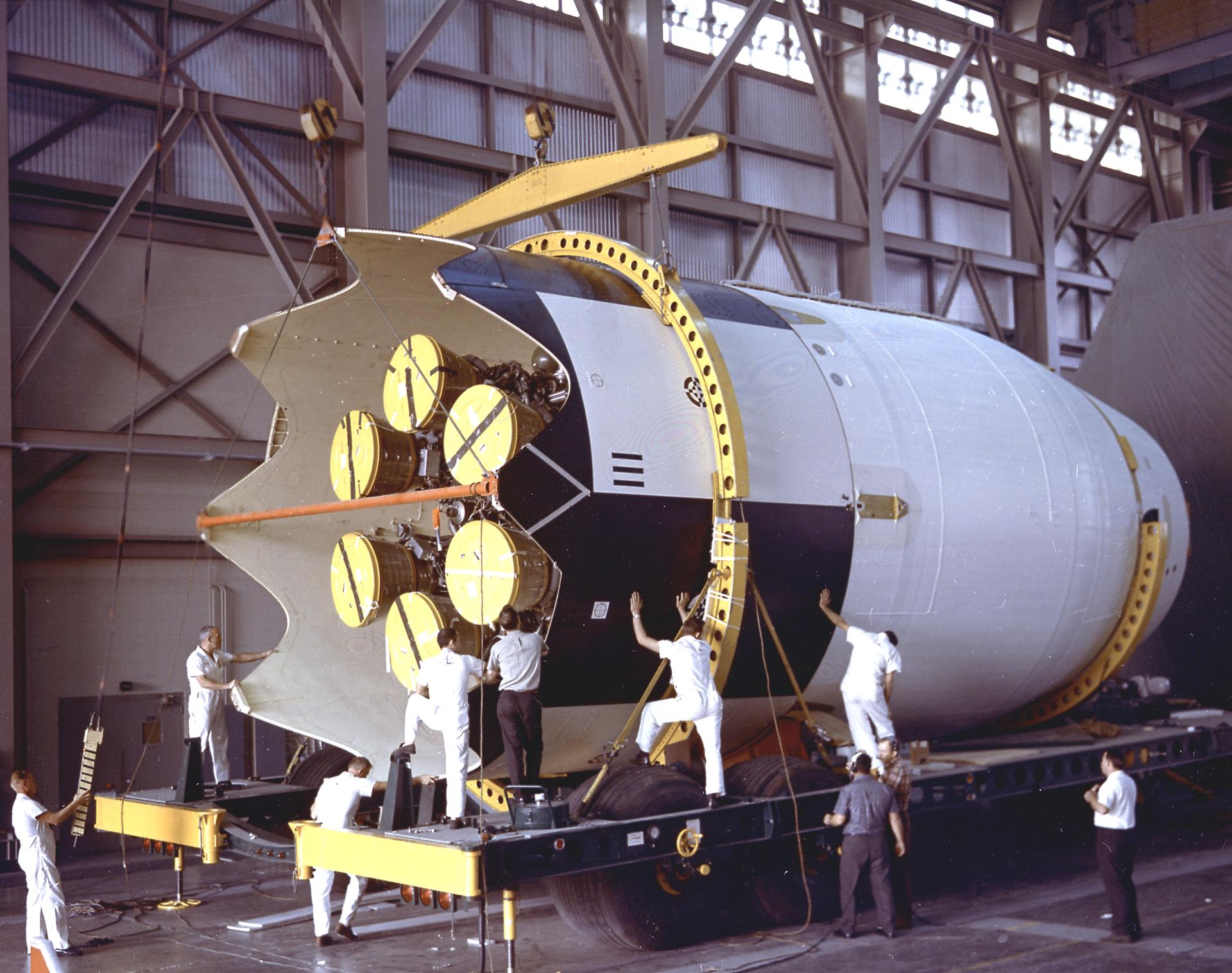

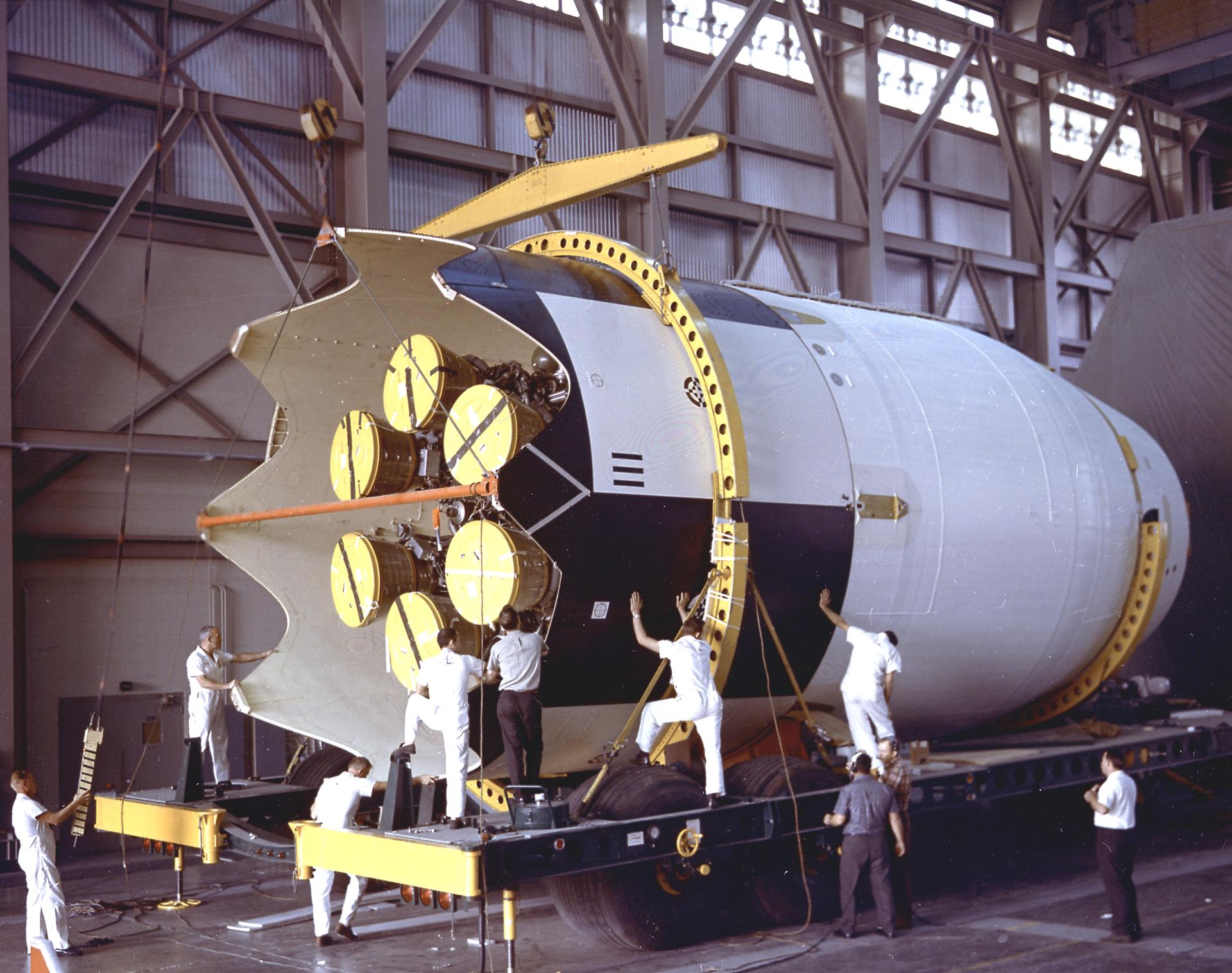

The S-IV stage for the SA-9 mission, undergoing weight and balance tests before launch. (Source: NASA)

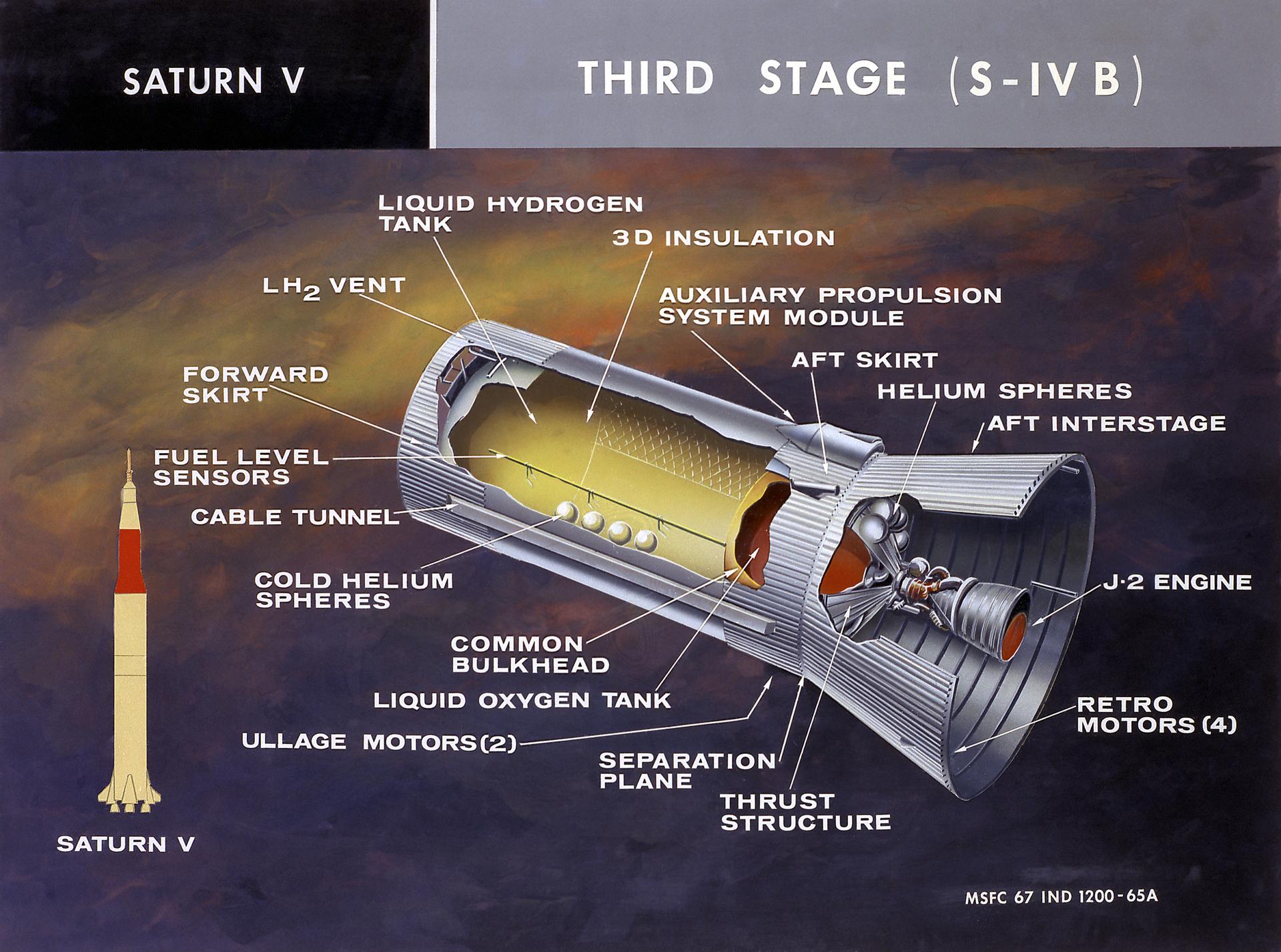

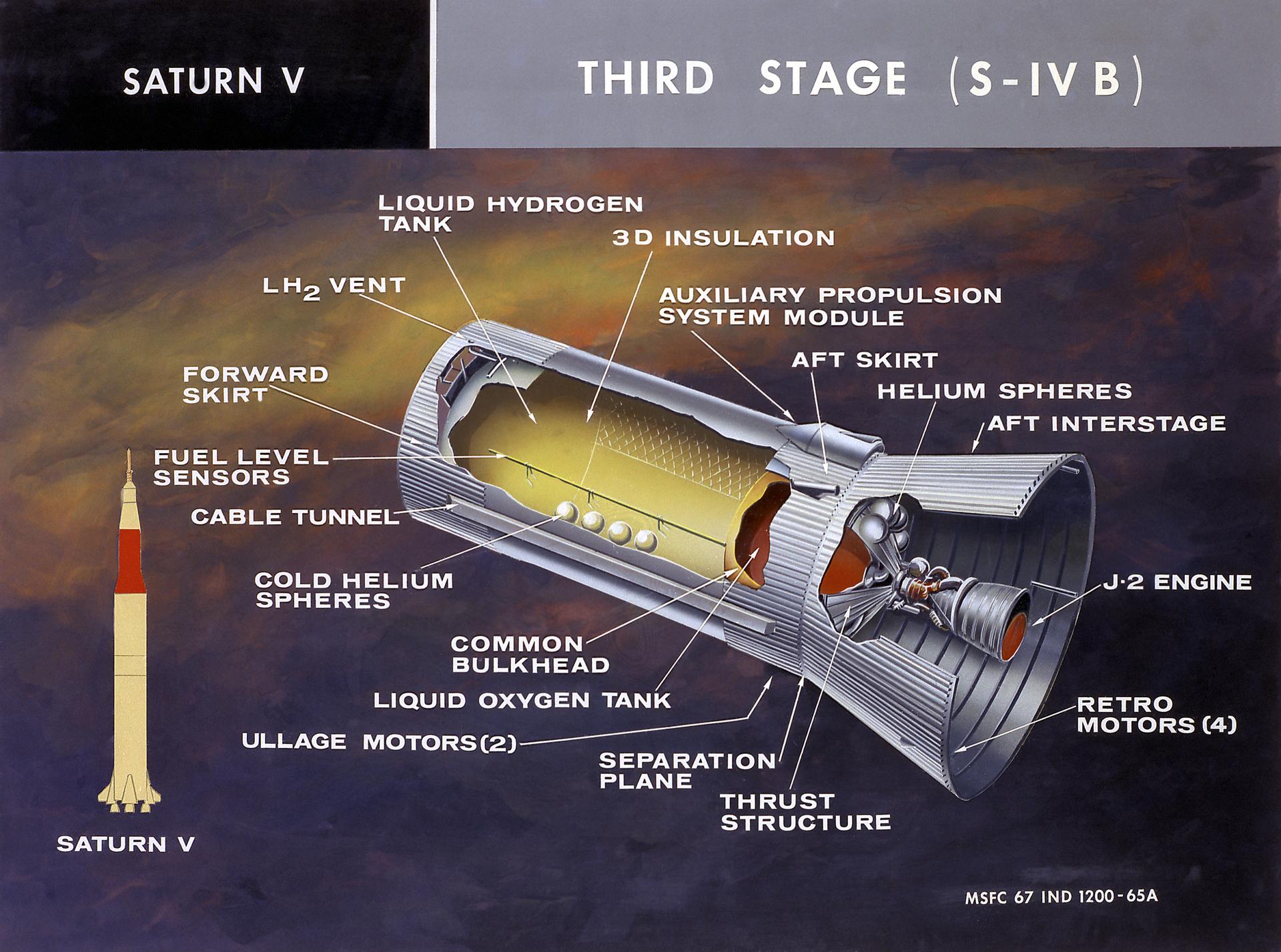

The upper stage of the Saturn IB and Saturn V was called the S-IVB. Although it had bigger tanks and a different engine (a single J-2), the stage was basically the same as the S-IV. The Saturn IB S-IVB had a thrust of 200,000 lb, while the Saturn V version had a little higher thrust and also needed to be restartable for the trans-lunar injection burn that would send the Apollo spacecraft on its way to the moon. Both versions of the S-IVB had their own thruster system, the Auxiliary Propulsion System, for attitude control during burns and the coast phase in Earth orbit before trans-lunar injection.

Cutaway drawing of the version of the S-IVB stage used on the Saturn V. (Source: NASA)

An S-IVB stage with a technician at Kennedy Space Center. (Source: NASA)

Douglas built the S-IV and S-IVB stages at a couple of facilities in southern California. The tank walls were milled in Santa Monica, then formed into a curve in large presses at Long Beach. Final assembly took place in Huntington Beach, in a specially-built factory building. The assembly building had external rather than internal bracing for cleanliness, because internal beams could provide a place for dust to gather before falling onto the stage and contaminating it.

Once the stages were complete, they were shipped up to SACTO for testing, either by barge or purpose-built aircraft, the Pregnant Guppy and Super Guppy.

Two S-IVB stages undergoing checkout at Huntington Beach. (Source: NASA)

The Pregnant Guppy transporting an S-IV stage. (Source: NASA)

Rocket testing at SACTO

SACTO had several test areas, named after letters of the Greek alphabet. The original testing area was the Alpha test site, which was first used for testing Thor rockets and then was converted to test S-IV stages. When it came time to test the S-IVB, Douglas built an all-new test site to the west, the Beta test site. At both sites, the rockets were test-fired in a vertical position in stands that consisted of a concrete base and a steel superstructure, which made the stand look rather like a shortened launch pad. The test areas also had propellant storage tanks and blockhouses for test personnel.

A smaller test area, the Gamma test site, was used for testing the Auxiliary Propulsion System. SACTO also had an administration area, with a Vertical Checkout Laboratory where stages were checked out before tests and sometimes stored afterward.

Most S-IV and S-IVB stages were tested at SACTO before they were flown. This was important for safety, because small flaws in manufacturing could lead to catastrophic destruction of a rocket stage. This happened more than once at SACTO, most notably on January 20, 1967, when S-IVB-503 blew itself to pieces in the test stand. S-IVB-503 had been slated for use on AS-503 or Apollo 8, the first manned launch of the Saturn V. Without static test-firing, the stage may have blown up in flight and killed the crew.

Two S-IVB stages at SACTO at the same time. The stage in the foreground was used in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project backup vehicle. It was never flown and is now on display at Kennedy Space Center on a Saturn IB. In the background, the Apollo 9 third stage is being installed in Beta Test Stand 1 for launch. (Source: NASA)

The Apollo 10 S-IVB stage being hoisted out of the Beta Test Stand 1 at SACTO after its static firing. (Source: NASA)

The Apollo 6 stage during static-firing in Beta Test Stand 1. (Source: NASA)

The interior of the Vertical Checkout Lab with an S-IVB. (Source: NASA)

The SACTO ruins in 2021

According to Sacramento’s Moon Rockets, a local history book that I read before visiting the SACTO site, the rocket testing stands were demolished in 2013 to make way for a housing development, after environmental remediation had made the area safe for development. As of 2021, though, no houses have been built on the old SACTO site, and there is no sign of any new construction.

The most intact part of the SACTO site is the administration area, which has been repurposed into a light industrial or commercial area called Security Park. The Vertical Checkout Lab still stands and is recognizable from photos from the 1960s. The administration building and guardhouse are also clearly 1960s vintage. There is even an old Douglas Aircraft Company sign standing outside of the gate, but there is no explanation about what it is doing there!

The SACTO Vertical Checkout Lab, still standing tall after all these years.

The 1960s-vintage guardhouse and Douglas Aircraft Company sign.

Security Park and the distant Sierra Nevada.

When I visited the SACTO site, I was disappointed, but not surprised, to see that the Beta test area for the S-IVB stages really does seem to have been demolished. I couldn’t actually see anything, and there was no place to stop for a closer look as I zipped past in my car on busy Douglas Rd. To my surprise, though, the Alpha test area still stands! The steel superstructure of the test stands have been demolished since the 1970s, but the concrete bases are still there, clearly identifiable through binoculars. The Gamma test site also seems mostly intact. It consists of a concrete structure with a series of bays for testing the thruster units; as such, it looks rather like a self-service car wash.

Wide-angle view of part of the former SACTO site. There just isn’t much here.

Annotated telephoto view of the remains of the Alpha test site.

Closeup of Alpha test stand 1 and the blockhouse.

The remains of the Gamma test site, where the APS were tested. The houses in the background were not there in the 1960s when SACTO was operational.

I was gratified to see that some of the ruins of the test site still stand. It was stupid and wasteful to tear down the Beta test site, because it has been eight years and the area still hasn’t been developed for housing. What was the rush to tear it down in 2013? At least the Alpha test site still stands. I hope it can be saved. Rather than being demolished, it should be stabilized and incorporated into the design of whatever housing development gets built there. It is a relic of a little-known time when Sacramento played a small but important role in the moon program.

Sacramento’s other Douglas (Logan) and SACTO

My father, whose name is coincidentally Douglas, spent his formative adolescent years in Sacramento, from the time his family moved there in 1964 to when he headed off to college in 1969. Like probably every engineering-minded kid in the 1960s, he followed the space program as it built up toward the first landing on the moon. He built model rockets and got up early to watch Gemini launches with a school friend.

But even though Douglas Aircraft Company was his neighbor in Sacramento, Douglas Logan had no idea that they even had a presence there, much less that they were testing rocket stages bound for the moon. When I told him about my visit to the SACTO site, he said that he had never heard about any Douglas rocket tests in Sacramento. All people talked about in those days was Aerojet, which was supposed to be a good place to get an engineering job.

After some thinking, though, my dad said that while he never heard people talking about the Douglas rocket tests, he probably actually heard the rockets being tested! He remembers hearing an indistinct roar off in the distance from time to time in the mid-to-late sixties in Sacramento. At the time, he thought the Air Force must be testing jet engines at McClellan Air Force Base—but prop planes were based at McClellan. What he heard must have been the rocket tests!

Apart from the noisy rocket test-firings themselves, Douglas must have kept a low profile in Sacramento. When my dad listened to the Apollo 8 broadcast on the radio at Christmastime 1968, or watched the Apollo 11 landing on TV in the summer of 1969, he didn’t know that the rocket stages that got both of those missions to the moon had been tested near his home in Sacramento.