Fifty years ago, every American who paid any attention to the news was familiar with George Wallace, four-term governor of Alabama and perennial presidential candidate. To many people who lived outside of Alabama—and especially outside the South—Wallace was a reactionary and antagonist, the stereotype of the race-baiting Southern Democrat and white supremacist. Baby Boomers like my parents remember Wallace’s calling for “segregation forever” in his inauguration speech in 1963, and then making a show of bodily blocking a doorway to oppose the desegregation of the University of Alabama. It was during Wallace’s first term as governor that vigilantes and law enforcement intimidated, beat up, and even killed civil rights activists. The villainous image of Wallace was passed down to later generations by that great repository of Boomer nostalgia, the 1994 film Forrest Gump, which features a scene set at the University of Alabama during Wallace’s desegregation protest.

As I found when I moved to Alabama for graduate school six years ago, Alabamians have more positive memories of George Wallace. He is not a villain but an influential, if flawed, leader. In his later terms as governor, Wallace reversed his stance on segregation and voting rights, and ultimately welcomed racial minorities into his administration. In 1972, while running for president, he was shot by a would-be assassin. The attack left him paralyzed below the waist. Popular memories of Wallace usually identify this attempt on his life as the Damascus Road experience that led to the reversal of his views on race.

It may be that Wallace had a real change of heart, but it is also true that he was, to his core, a politician who always knew what would appeal to voters. His first bid for the governorship, in 1958, ended in defeat when his integrationist platform was a flop with Alabama’s overwhelmingly white electorate. Between this defeat and his first victory four years later, Wallace reinvented himself as a segregationist, the image that would define him for so many Americans outside Alabama. By 1972, Alabama’s African Americans had been enfranchised by the Voting Rights Act, and Wallace needed black votes to stay in office. An accurate image of Wallace is neither a racist, nor a man who (like Darth Vader?) became good in the end. Rather, he was a cunning politician and a populist, who played to the fears of voters.

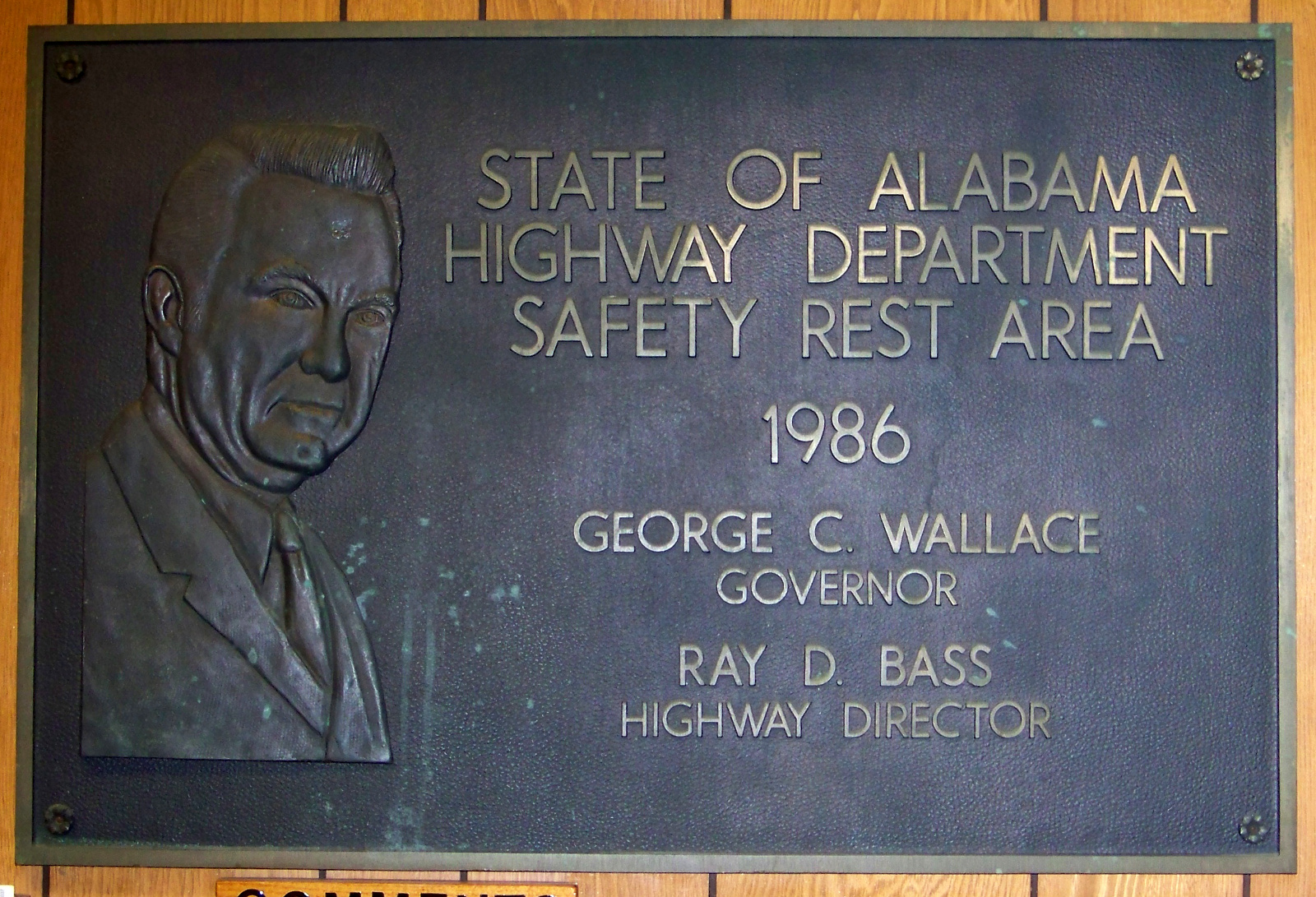

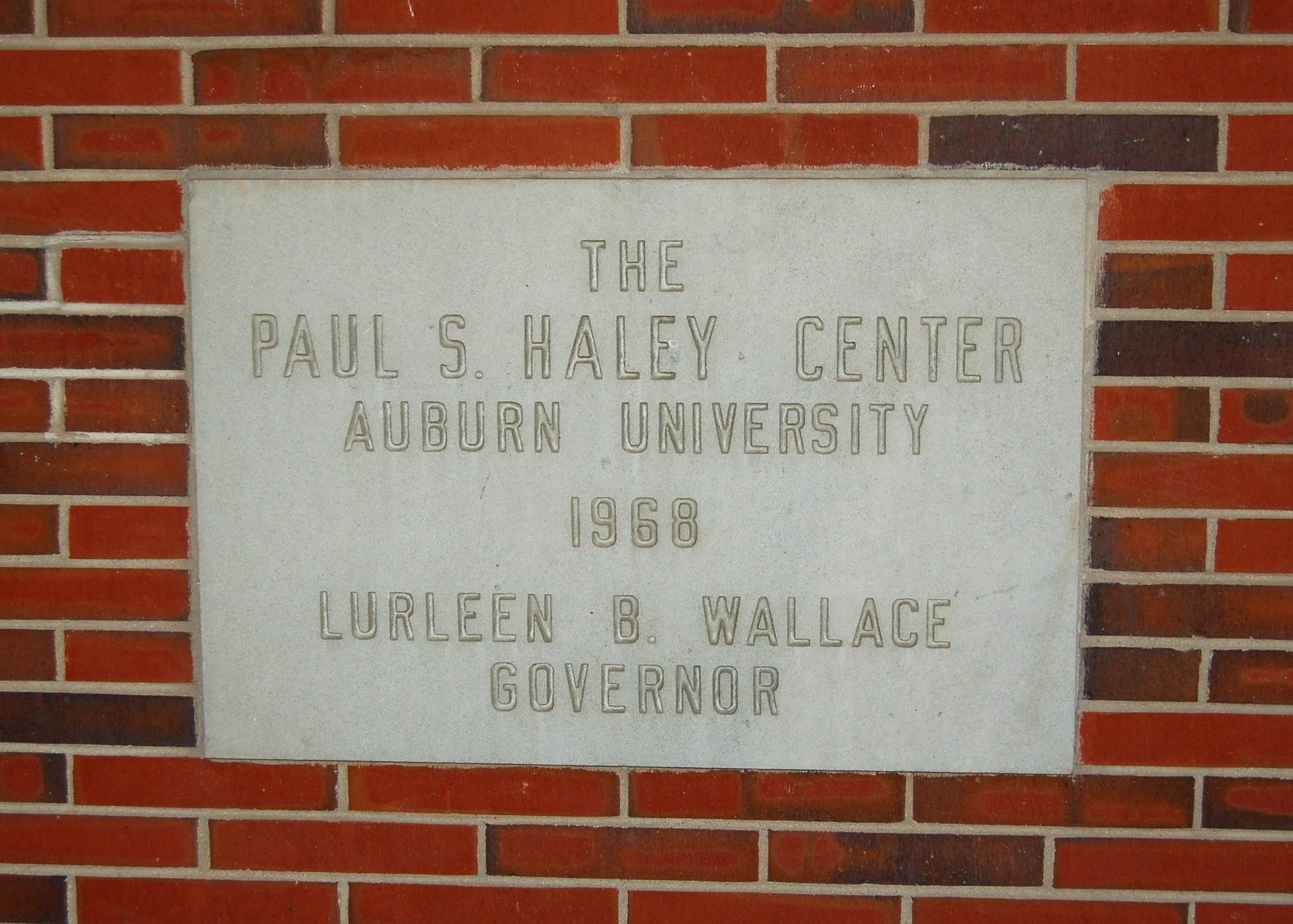

Six years ago, George Wallace’s name and image were everywhere in Alabama. Wallace’s likeness stared out from plaques at rest areas on Interstate 85, which was constructed during his tenure as governor. On the campus of Auburn University, where I studied, several of the prominent buildings were built in the Wallace era. On my way to assist for history classes in Haley Center each day, I walked by a plaque with the name Lurleen Wallace, George’s wife who won election handily in 1966 when he was forbidden by state law from running for a second consecutive term. I occasionally went to the architecture library in Dudley Hall, which had a plaque of George Wallace himself.

The rotunda of the state capitol has spaces for four portraits of governors. In 2011, I was surprised to find that only two of the spots were occupied by recent governors; the other two featured George and Lurleen Wallace. The capitol tourguide claimed that these paintings were on permanent display because George was Alabama’s longest-serving governor, and Lurleen was the state’s first “lady governor.” To me, this seemed like a rationalization, the real reason being the state’s Wallace cult.

Two years after moving away from Alabama, I recently returned to attend commencement, and I used the opportunity to reacquaint myself with the state. I was surprised to find that George Wallace was much less visible in 2016 than he had been earlier. The plaque at the Alabama Welcome Center on I-85 was hidden behind a brochure rack and a Christmas tree. The portraits in the rotunda of the state capitol were gone, having been replaced by more recent governors. At Auburn, Lurleen’s plaque on Haley Center was still in place, but George’s plaque on Dudley Hall had disappeared entirely. The building was recently remodeled, and the plaque didn’t survive the renovation.

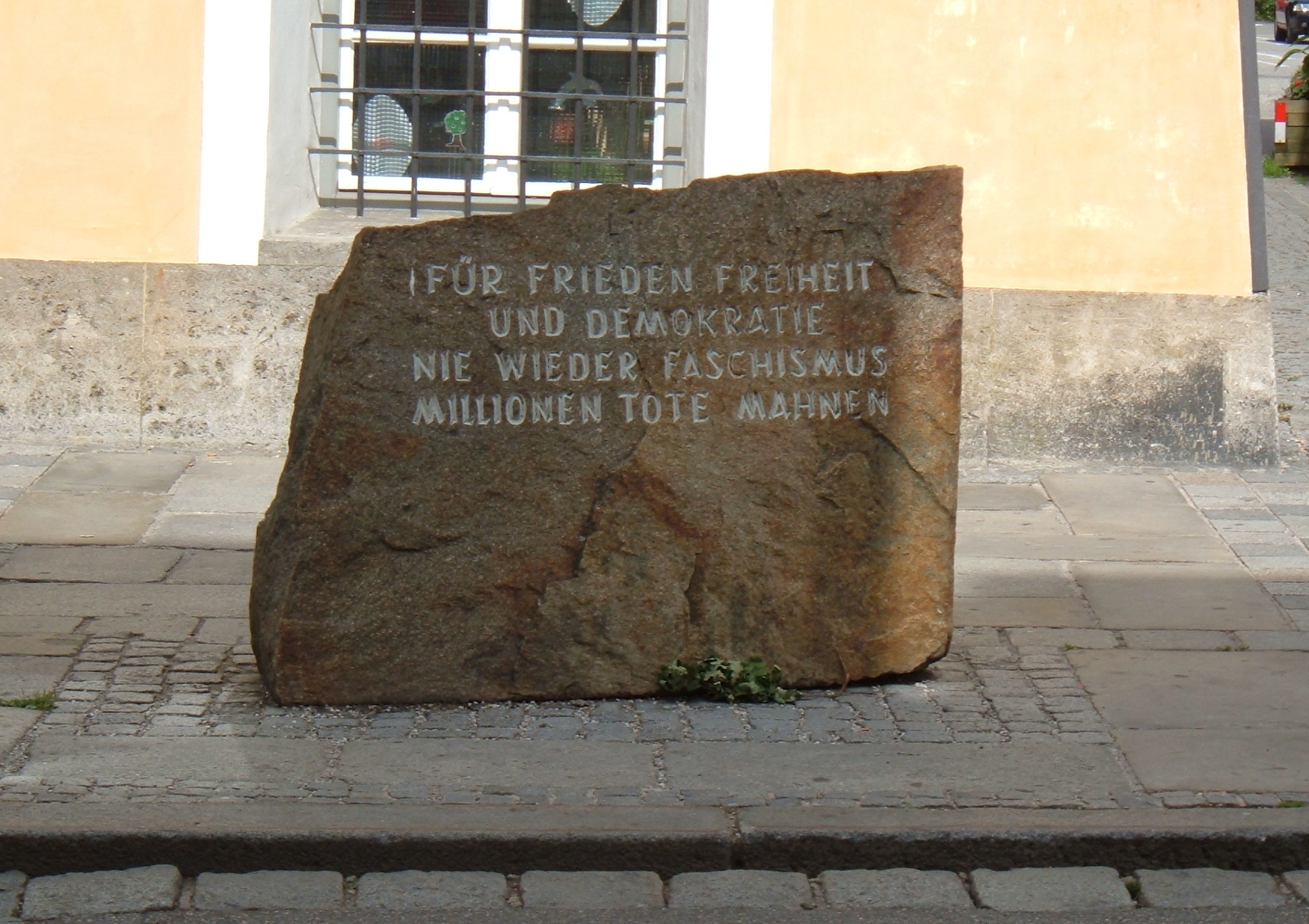

The ghost of George Wallace has finally been served its eviction papers. Good riddance, I say. Even though George Wallace was not the meat-headed segregationist and racist that many people remember, he did support views like this for much of his political career, and by memorializing Wallace, it seemed as if Alabama was giving tacit approval of the ugly parts of the governor’s legacy. Alabama shouldn’t forget either the good or bad things Wallace did, but he has no right to be a hero. I’m glad to see that Alabama has begun to move on from the cult of Wallace.

Links

- Time marches on: Portraits of George and Lurleen Wallace removed from Capitol rotunda (AL.com)

- George Wallace Jr. to Oprah: ‘Selma’ portrayal of my father is ‘pure, unadulterated fiction’ (AL.com). An example of the positive view of Wallace held by many Alabamians. George Jr. glosses over the fact that his father did not begin his career as a segregationist.