Except for the Bear Flag Revolt, the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 isn’t much remembered or talked about north of the border. The war is commemorated by no holidays and I know of no major monuments to it. In fact, it is so far removed from our collective memory that I had never even heard about it before my 11th grade American Studies class.

South of the border, it is another story. Even if the events of the United States Intervention (as the war is called in Mexico) are often confused in popular memory with the French Intervention of the 1860s, everybody knows about how the Yankees invaded Mexico and annexed the northern part of the country to the United States. Probably every city in the republic has a street named after the Ninos Héroes (“Boy Heroes,” explained below).

The Mexican-American War was started by President James K. Polk, an expansionist southerner who was obsessed with the idea of getting control of California. When diplomatic channels failed to yield a Mexican cession of California and New Mexico, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor into disputed territory between Texas and Mexico to pick a fight with Mexico. Once the war was on, American forces invaded and occupied northern Mexico, but the Mexican government did not capitulate as Polk hoped. So Polk sent General Winfield Scott to invade the Mexican heartland at the port of Veracruz. After taking Veracruz, Scott’s forces fought their way up into the central Mexican highlands to Mexico City. With the defeat of forces defending the capital city, the Mexican government capitulated and signed away its claims to California and New Mexico.

Now, 171 years after the end of the war, Mexico City is still thick with monuments and memory of the United States Intervention. On a trip to Mexico City in June, I went in search of sites and memorials of the war, in an attempt to better understand the conflict itself and how it has been remembered in the years since. Not surprisingly, there is no heritage trail, so I had to piece together my own from what I already knew about the war. Here is what I found.

The Pedregal

Mexico City is located in the Valley of Mexico, surrounded by hills and mountains on all sides. General Scott’s forces entered the Valley of Mexico on August 7, 1847 through a 10,000-ft-high pass in the south. Mexico City is now a giant metropolis that sprawls across the valley, but it was much smaller then. Between the pass and the city, one contingent of US forces (led by a certain Captain Robert E. Lee) advanced on the city across a wasteland of lava flows know as El Pedregal (The Rocky Ground).

The Pedregal remained a useless wasteland for a hundred years after the Mexican-American War, when the area was developed as a posh housing development known as Jardínes de Pedregal. Most of the Pedregal is thus locked away in private land, but some of it is taken up by Mexico’s premier university, UNAM. Surviving lava flows in the campus have been incorporated into the landscaping, allowing one to get a sense of the kind of terrain that the American invaders crossed on their way to Mexico City.

Your blogger sitting on a surviving piece of the Pedregal on the UNAM campus. (Photo by Verónica Trinidad Gallegos.)

Monument to the Sanpatricios

Not far from UNAM is San Ángel, a colonial city that has been engulfed in Mexico City’s urban sprawl. Some parts of San Ángel retain their colonial character, and one such place is San Jacinto Plaza. The plaza features a monument to one of the more interesting participants in the war, John Riley.

John Riley was an immigrant to the United States from Ireland by way of Canada. Just before the war started in 1846, while serving as a sergeant in the US Army, Riley deserted to Mexico. He would go on to lead the Batallón de San Patricio (St. Patrick’s Battalion), composed largely of other Irish-Catholic deserters fighting against the Americans. The Sanpatricios were defeated at the Battle of Churubusco outside of Mexico City, and many of the deserters were executed in a mass hanging. Riley himself escaped this fate because he had deserted before the outbreak of war, but he was branded with the letter D on his cheek (for deserter).

(Aside: Churubusco is a Mexican-American War site that I missed. The historic battlefield is now home to a museum about interventions in Mexico by the Americans, French, and other foreign powers in the nineteenth century.)

The Sanpatricios were widely reviled in the US Army, particularly by loyal Irish-Americans. Later in the nineteenth century, the War Department refused to acknowledge that they had even existed. But they are remembered fondly in Mexico and Ireland. On opposite sides of the street at San Jacinto Plaza are a commemorative plaque placed in 1959 and a bust of Comandante Riley dedicated in 2010 by the Irish ambassador. (He is also the subject of a mediocre TV movie, One Man’s Hero.)

Monument to Comandante John Riley of the Sanpatricios, erected in 2010.

Plaque honoring the Sanpatricios in San Ángel, placed in 1959.

Molino del Rey

The final thrust into Mexico City began on September 8, 1847 with the Battle of Molino del Rey. The Americans had received intelligence that the Mexicans were recasting church bells at Molino del Rey, a mill outside the city. A force sent to stop this arms production defeated the Mexican defenders, but with heavy casualties. (It turned out that the intelligence had been faulty, and no cannons were being made there.)

The old mill building known as Molino del Rey still stands on the edge of Bosque Chapultepec, the central park of Mexico City. Until last December, Molino del Rey was locked away from the public in the compound of Los Pinos, the official residence of the President of Mexico. But then the newly-inaugurated president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, opened Los Pinos to the public. Molino del Rey was made accessible as well. The general public can’t go inside, because the building is used by the Mexican military, but you can get a good enough view of it from outside.

View of the front side of Molino del Rey. In the foreground is a restored sixteenth-century aqueduct.

Backside of Molino del Rey.

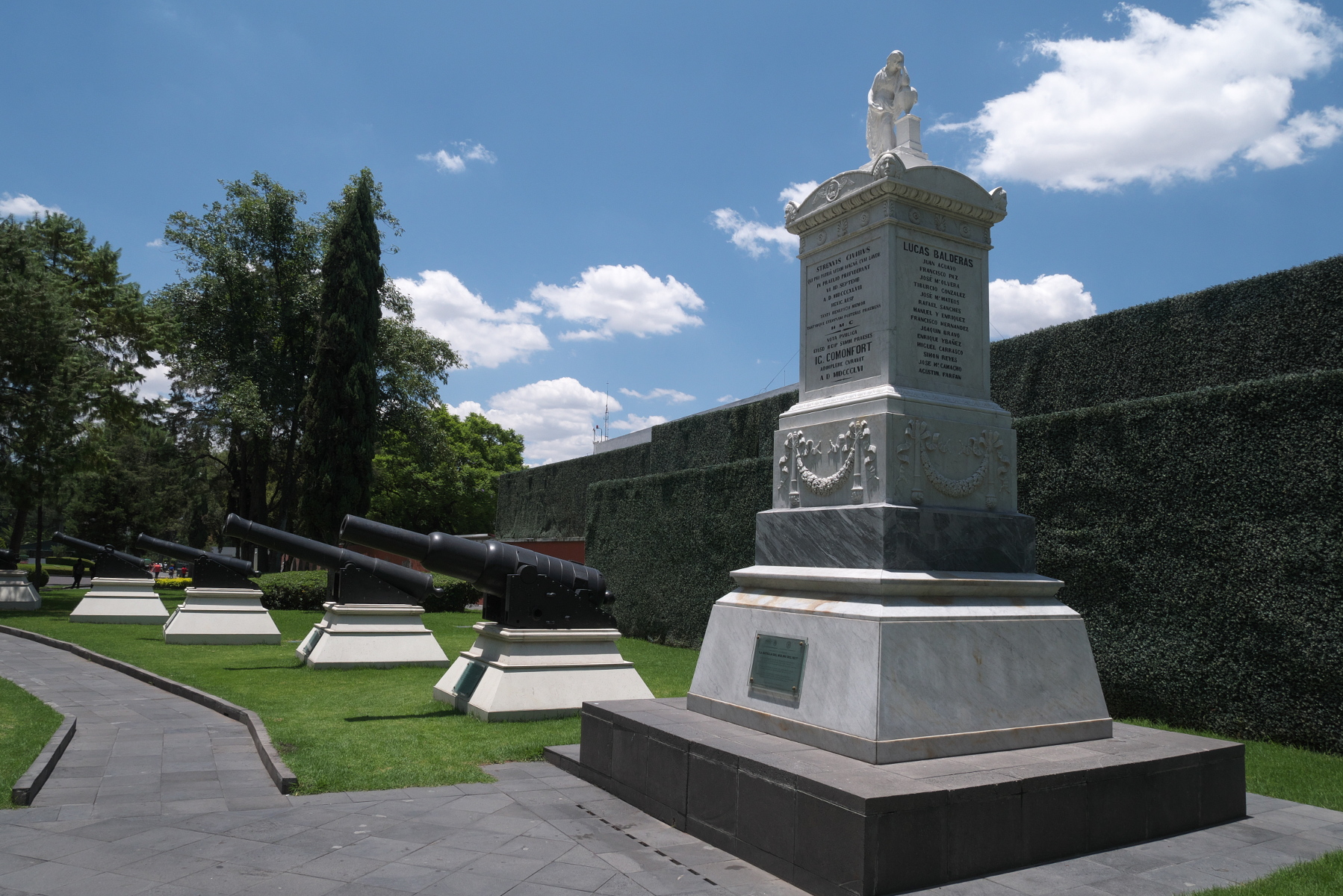

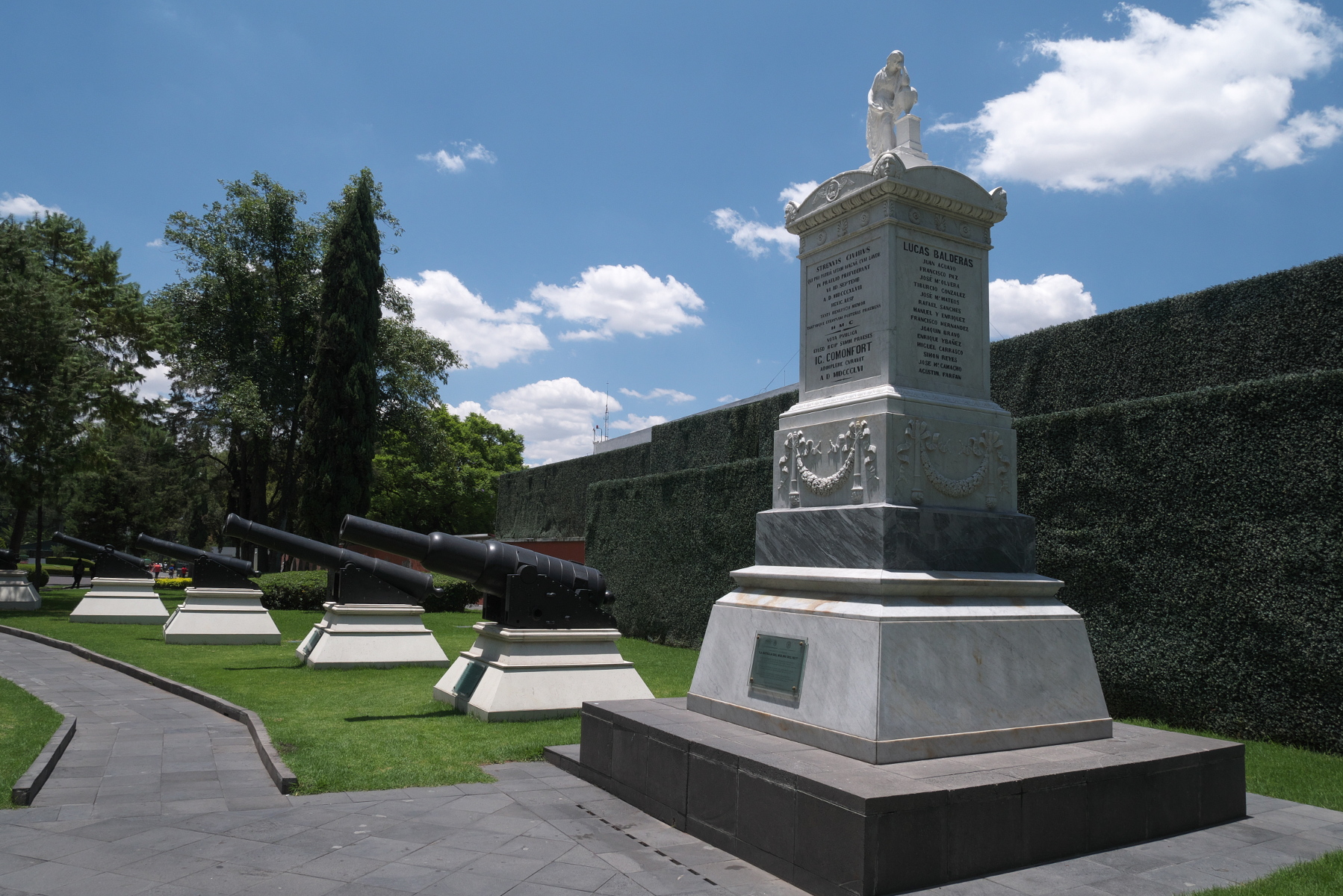

Monument to the battle of Molino del Rey, erected 1856 and restored 2014.

Castillo de Chapultepec

The last great battle of the Mexico City campaign took place at Chapultepec Castle, perched on a hilltop not far from Molino del Rey. The castle had been a residence of the Spanish viceroy, and it 1847 it was being used by the Military Academy of Mexico. On September 13, 1847, the American attackers bombarded the castle before using scaling-ladders to reach the summit of the hill. Famously, six teenaged cadets died defending the castle alongside the regular troops. They became known as the Niños Héroes (Boy Heroes), who are commemorated across the country.

Chapultepec Castle is now a terrific history museum, tracing the story of Mexico from Aztec times through about 1920 with the end of the Mexican Revolution. The museum has an excellent collection of artifacts that are attractively displayed. One room of the museum is devoted to the Mexican-American War, complete with a shrine to the Niños Héroes.

Facade of Chapultepec Castle.

This painting on the ceiling of the main hall in Chapultepec Castle portrays Juan Escutia, one of the Niños Héroes, falling to his death with the national flag wrapped around him. Painted by Gabriel Flores.

At the foot of the hill below the castle are two monuments to the Niños Héroes, a modest one dedicated in 1881 and a much bigger one at the entrance to the park, which was completed in 1952.

Old Niños Héroes memorial, erected 1881. US President Harry S. Truman placed a wreath at this monument in 1947.

Newer Niños Héroes monument, dedicated in 1952.

The Zócalo

With the fall of Chapultepec, the way to Mexico City lay open. Not wanting the battle for the city to devolve into house-by-house fighting and looting, General Scott diverted his troops to the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo to the north. There the Americans set up their headquarters and waited for the Mexican government to surrender, which it did. The Mexican government decamped to the city of Querétaro, and on the morning of September 14, General Scott’s troops paraded in triumph into the Zócalo, the central square of the city. Marines took control of the National Palace and raised the US flag over it (referenced as the “Halls of Montezuma” in the Marine Corps Hymn).

A famous illustration by Carl Nebel depicts Scott’s forces parading on the Zócalo, with the Metropolitan Cathedral and National Palace in the background. The Zócalo looks much the same now as it did in 1847, at least from Nebel’s viewpoint. But with today’s crowds of tourists and noisy automobile traffic, it is hard to imagine the defeated, humiliated city that General Scott and his forces entered.

Illustration by Carl Nebel of American troops parading in the Zócalo. (Source: Wikipedia, public domain.)

Your blogger standing on just about the spot where the white horse is located in Nebel’s illustration. (Photo by Verónica Trinidad Gallegos.)

Guadalupe Hidalgo (now Villa de Guadalupe)

The US military would occupy Mexico City for eight months, the first time that American forces ever occupied an enemy capital. The official end of the conflict came with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed by the Mexican government and American occupiers on February 2, 1848. As part of the treaty, Mexico signed away its claim to the northern 42% of its territory, including California and New Mexico. The bitter defeat would lead to a brutal internal war in Mexico a decade later, the War of the Reform. In the United States, the glut of new territory exacerbated tensions over the question of slavery; these tensions would also lead to a devastating war, the American Civil War of 1861-65.

Guadalupe Hidalgo is now known as Villa de Guadalupe. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in the old Basilica of Guadalupe, built in 1709. Although replaced by a grand modernist building in 1976, the Old Basilica—renovated and now hopefully earthquake-safe—still stands in Villa de Guadalupe.

Your blogger in front of the old Basilica of Guadalupe (on the left with the yellow roof). (Photo by Verónica Trinidad Gallegos.)

Old and new Basilicas of Guadalupe, viewed from Cerro Tepeyac.