In my first quarter teaching at Pacific Union College in Napa County, California, I got assigned an upper-division class about medieval Europe. PUC is close to a wide range of educational resources, as it is located within striking distance of San Francisco, Sacramento, the Pacific Coast, and the Sierra Nevadas. Had I been teaching California history, I might have considered taking my class to Mission Dolores in San Francisco, or perhaps the barracks at Sonoma. But when I was planning my class about the Middle Ages, it never crossed my mind that there might in fact be resources related to medieval Europe in the area as well.

Then, once the quarter was well underway, I discovered that San Francisco has its very own (neo-) Gothic cathedral, standing atop Nob Hill and looking at least a little like the great churches built in England, France, Germany, and elsewhere in Europe during the High Middle Ages. All of a sudden, it occurred to me that there might be other relics of the Middle Ages in San Francisco as well—whether authentic or, like this cathedral, mere imitations. It was much too late in the quarter to incorporate San Francisco into my curriculum, and at any rate, I didn’t have time to catch my breath while teaching three classes for the first time. But after the quarter finished, I set off to investigate whether San Francisco—a North American city founded in the eighteenth century—could teach me something about medieval Europe.

Grace Cathedral

The first stop on my medieval San Francisco tour was Grace Cathedral, the church on Nob Hill. Built in stages from 1927 to 1964, Grace Cathedral has a structure of steel and concrete that is designed to be earthquake-safe. The architecture is primarily based on French Gothic examples, although certain elements were taken from Spanish and English churches.

Although work on the church stopped in 1964, it has never really been finished—in much the same way that many medieval cathedrals were left incomplete. The vaults of the nave have not been filled in, and many of the wall and column surfaces are bare concrete. The parts of the church that have been completed look terrific; the rest, less so.

The apse of Grace Cathedral. I’m not sure why that little bit of vault at the very top of the picture has been filled in while the rest has been left open.

The most impressive part of the cathedral for me was the Chapel of Grace, which has been completed in its entirety. It has an early-modern altarpiece.

Along the walls in the aisles are murals illustrating a variety of scenes, including the construction of the cathedral and the founding of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.

The cathedral is full of art, ranging from an actual medieval Spanish crucifix to a triptych completed in 1990 by Keith Haring.

I was also surprised to discover that the cathedral has copies of the doors of the bapistry at the cathedral in Florence, a famous piece of art from the early Renaissance. The doors in San Francisco were made from casts of the originals taken during World War II.

Portal of Santa María Óvila

The next stop on my tour was the campus of the University of San Francisco, a Jesuit institution on the western side of the city near Golden Gate Park. An outdoor theater in the back of Kalmanovitz Hall has a portal from Santa María de Óvila, a Cistercian monastery built in Spain between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. By the twentieth century, the monastery had fallen into disuse, and in the 1930s, newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst bought large parts of it and had the stones crated and shipped to San Francisco. Although he planned to rebuild the monastery on one of his estates, that never happened, and the disassembled stones spent decades in Golden Gate Park. The de Young Museum assembled just the monastery’s church portal in 1965, but this was transferred to USF after the museum opened a new, earthquake-safe facility.

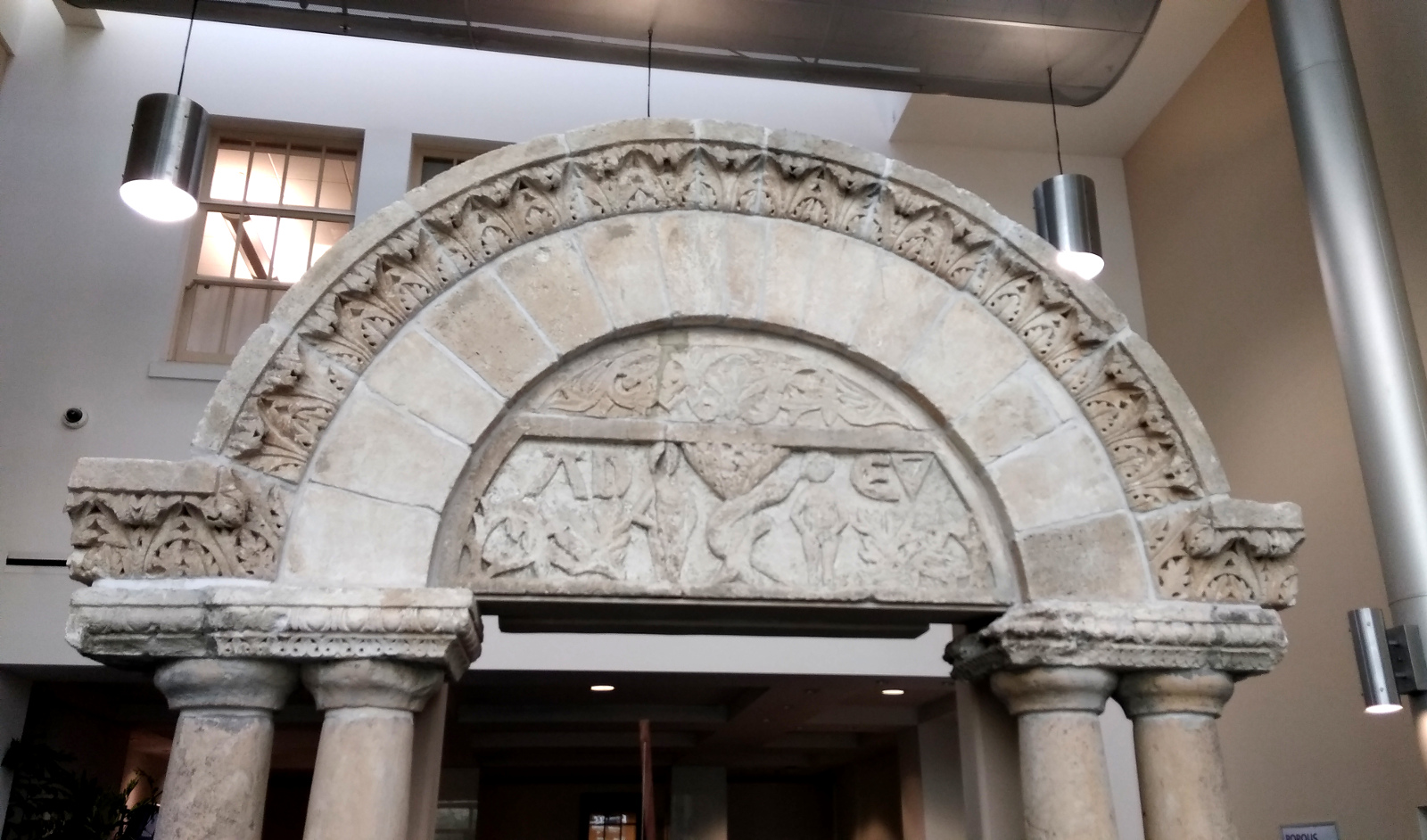

As a bonus, right inside Kalmanovitz Hall is another bit of medieval architecture, identified by a plaque on the wall as a “twelfth century Italian Romanesque portal.” It was gifted to USF by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (the Legion of Honor and the de Young Museum).

By the way, the rest of the stones for Hearst’s monastery were eventually transferred to New Clairvaux, a working Cistercian monastery in the Sacramento Valley. The stones were made into a new chapter house, which opened in 2012.

Modern statues of medieval warriors at the Legion of Honor

The last stop on my medieval San Francisco tour was the Legion of Honor, an art museum on a hilltop overlooking the Golden Gate and the city.

In front of the museum are two modern statues of medieval warriors: Rodrigo Díaz and Jeanne d’Arc.

I was especially interested in the statue of Rodrigo Díaz a.k.a. El Cid, an eleventh-century soldier of fortune who was exiled from his native Castile and set up an independent principality in Valencia. In the first medieval history class I taught, I had my students read The Song of the Cid, a twelfth-century fictionalization of El Cid’s life and career.

The Legion of Honor’s statue of El Cid astride his horse Babieca was sculpted by Anna Hyatt Huntington in 1921. This cast was made about six years later.

Anna’s husband Archer had translated The Song of the Cid into English, and this sculpture seems to be based on the fictionalized character in the epic.

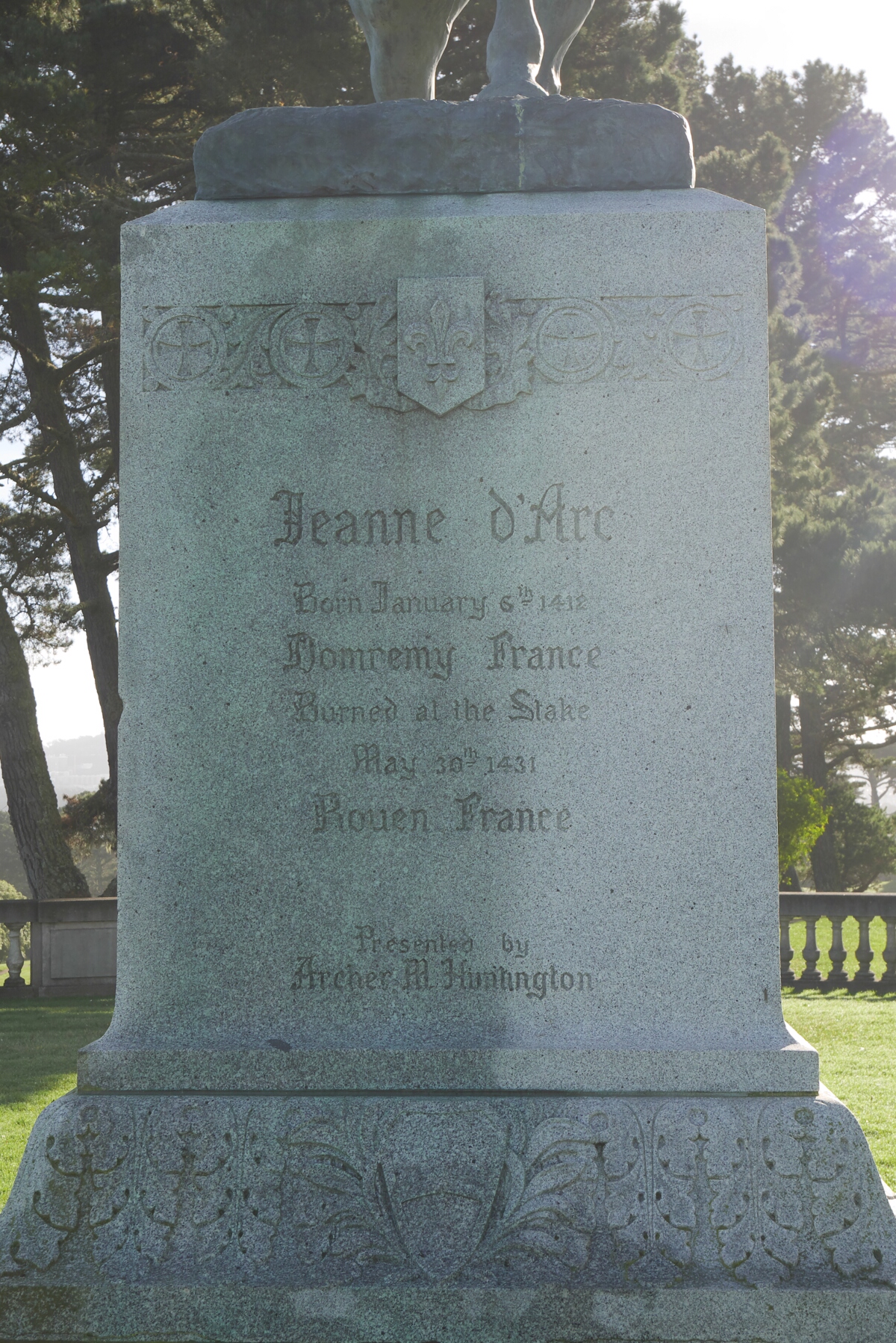

The other statue, also by Anna Hyatt Huntington, is Jeanne d’Arc, better known in English as Joan of Arc, the French peasant who led her people to some morale-boosting victories against the English in the Hundred Years’ War. I’d had my students read Joan’s threatening letter to the English, and I had just watched the Luc Besson film The Messenger (1999), so Joan was on my mind too.

Joan of Arc is going to have trouble fighting the English without the blade of her sword. Just saying.

The design of Joan’s armor seems to be based on a fifteenth-century miniature painting of her.

Real-life medieval artifacts inside the Legion of Honor

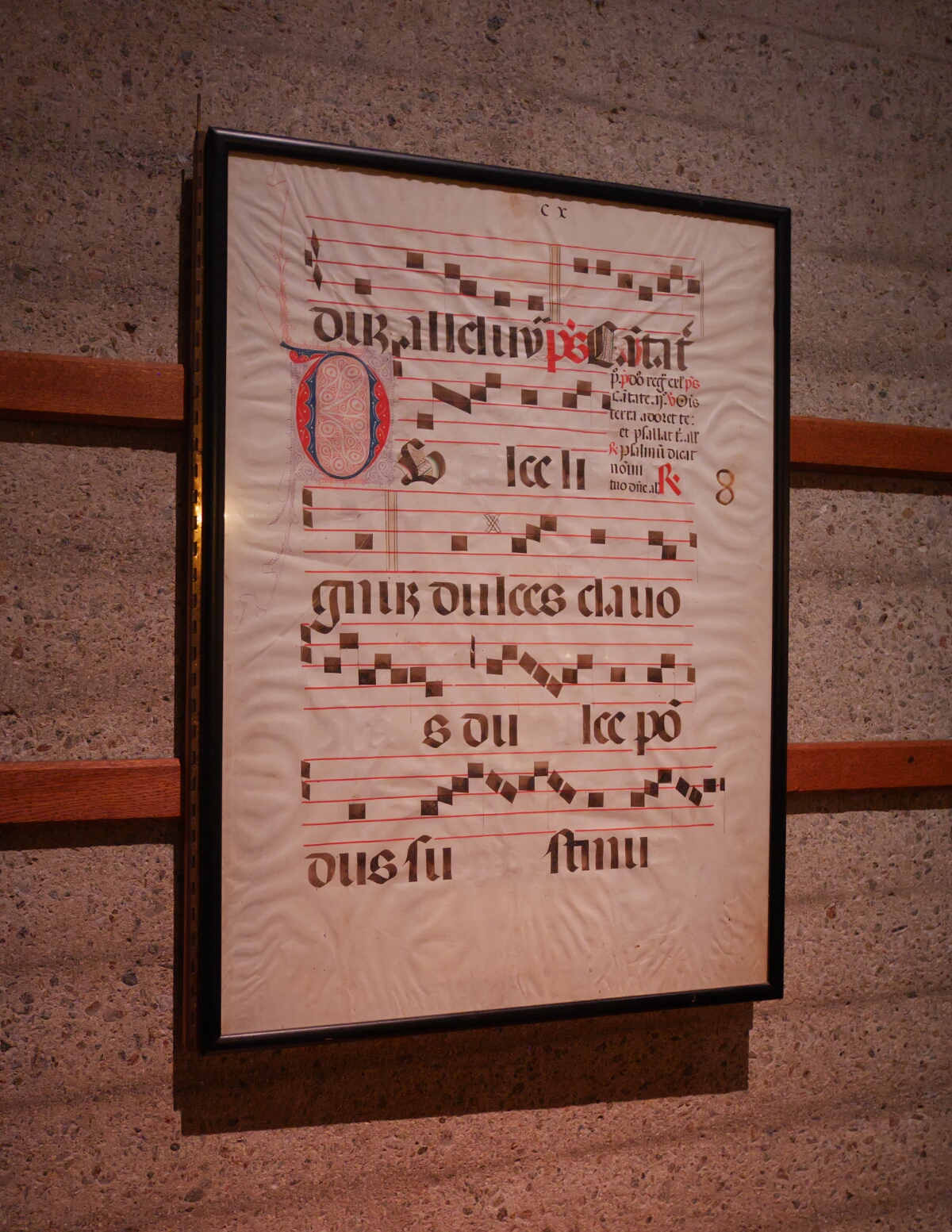

Inside the Legion of Honor museum, there is a gallery of actual medieval artifacts.

Ceiling from the Palacio de Altamira, fifteenth-century Spain. This remarkable piece of architecture shows clear Moorish influence.

Thus ended my tour of medieval San Francisco. As it turns out, San Francisco does have something to tell me about the Middle Ages in Europe. Despite being a modern building, Grace Cathedral got me thinking about what it might have felt like to visit one of the great cathedrals during the High Middle Ages. Anna Hyatt Huntington’s statues of El Cid and Joan of Arc made me consider how we remember and make use of the medieval past. And at USF and the Legion of Honor, I got to see actual relics of the Middle Ages in Europe. These places made me think about the Middle Ages in different ways than I could have by just looking at books. They could inspire my students to think differently as well.