For at least a thousand years, people have been building large structures out of stone in northwestern India. The modern Indian state of Rajasthan is full of the remains of these monuments. Most of the monuments—fortresses, palaces, tombs, cenotaphs, and the like—have no real use anymore, except maybe as tourist attractions. There are plenty of pre-modern temples still in use, although many of them have been altered beyond recognition over centuries of use. And then there are some pieces of infrastructure that, with proper maintenance, still serve their original function hundreds of years after they were built.

One example is a bridge over the Gambhiri River in the town of Chittaurgarh in southern Rajasthan. The bridge is located on the main road into town. It is built entirely of stone, with nine slightly-pointed arches and one semicircular arch. (The river flows through eight of the arches, while the remaining two are on the shore. There are also two additional arches on each side of the bridge, but these are made in a different style and seem to have been added later.) The piers founded in the river have triangular projections on the upstream side, to help the river water, and any debris that might be floating in it, flow smoothly around the bridge.

The Rajasthan state Department of Archaeology and Museums has set up a Hindi interpretive plaque on the western side of the bridge. According to the plaque, the bridge was built early in the fourteenth century by Khijra Khan, after his father Alauddin Khilji captured Chittaurgarh in 1303. The bridge is built partly of stone blocks appropriated from other buildings. Inscriptions of Tej Singh and Samar Singh, two late-thirteenth-century rulers of Mewar, are still visible on the bridge. There are also some surviving architectural flourishes from the original structures, including designs of flowers and leaves. (None of this is visible to the casual observer from the shore, but I trust that the state archeologists know where to look.)

The Gambhiri River Bridge has been modified a little over the past seven hundred years. Although it was designed for horses and carts, it is strong enough to support motor vehicles. In modern times, a three-foot railing was added to the side of the bridge; when this proved inadequate for whatever reason, an eight-foot fence was also added. The bridge also carries several pipelines and some cables. Just downstream, a newer bridge has been built for eastbound traffic. The medieval bridge now just carries westbound traffic away from Chittaurgarh.

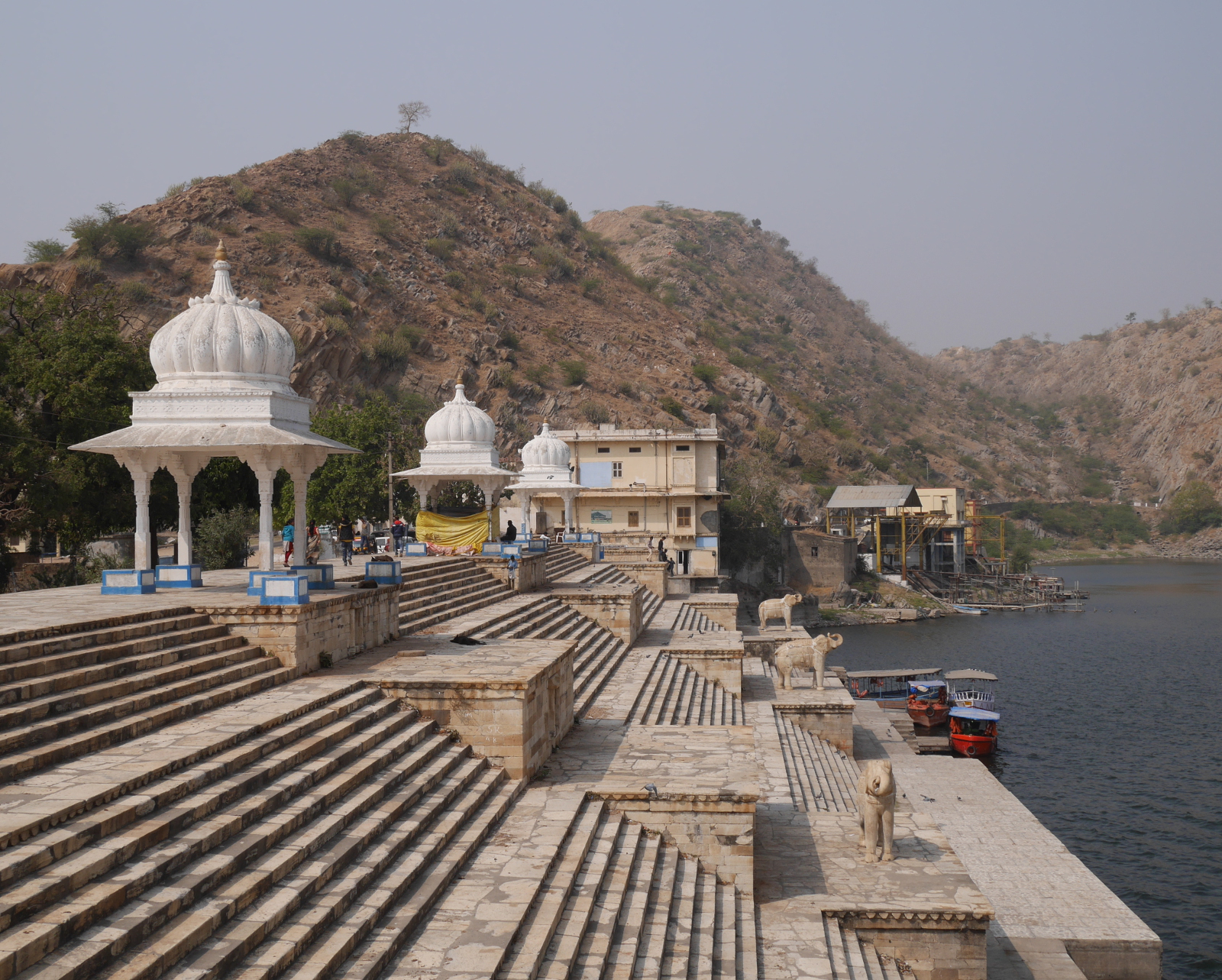

For readers who aren’t familiar with Chittaurgarh: The place is famous for the fortress by that name, a massive structure stretching five kilometers along the top of a ridge. The fortress was defensible, thanks to its position, but it was also a highly sought-after strategic prize, and it was captured and re-captured several times throughout its long history. Emperor Akbar won the fort for the Mughal Empire in a long and bloody siege in 1567-68. The fortress is now maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India, although it is so huge that inhabited villages exist within the walls alongside the historical monuments. Architectural highlights inside the fort include the Vijay Stambh (Tower of Victory, 1457-68), Kumbha Shyam Mandir (magnificent Nagara-style temple), Mira Bai Mandir, and Gaumukh Kund (rainwater storage tank).