Kolkata (or Calcutta, as it is still sometimes spelled), the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, was once the capital of British India. After 1912, when the capital moved to Delhi, most imperial institutions also relocated once new facilities were ready for them. The Imperial Records Department, for instance, moved from the Imperial Secretariat Building in Calcutta into its own building designed by Edwin Lutyens in the new capital. (After independence, the IRD became the National Archives of India.) But even as most institutions moved, some stayed behind, and one of these was the Imperial Library. Renamed the National Library of India (NLI) after independence, it is today the largest library in the country.

I had the privilege of spending two weeks at NLI while doing research for my dissertation in 2015. Of the three major institutions I visited for research in India (the other two were NAI and the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library), the National Library was certainly the easiest to find and navigate once I was there. My Rough Guide tourbook had a listing for NLI, including details on registration requirements. The people at the India Tourism office told me how to get there, by catching the 230 bus from Esplanade. Upon registration at the library, I received a full-color orientation booklet, with details of the different buildings at the complex and what can be found in each.

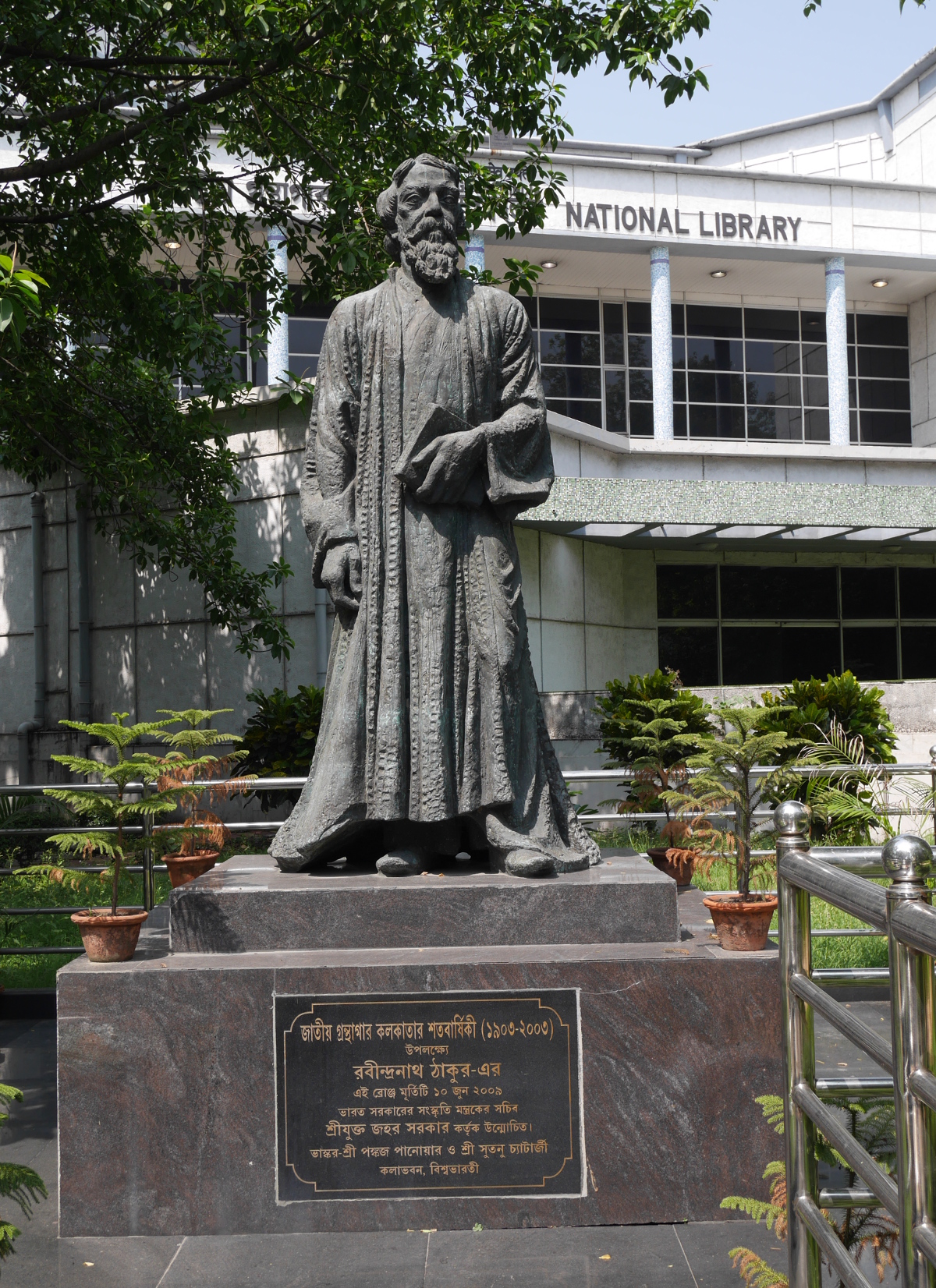

The National Library of India is located south of the city center at the Belvedere Estate, a big landscaped compound with a former imperial residence in it. The Belvedere House, as the residence is known, had once been occupied by Warren Hastings and (much later) was the main library building after independence, but in 2015 it was much the worse for wear and was being restored by the Archaeological Survey of India. The current main library building, Bhasha Bhawan (Language Building) is in the back of the compound. It is an attractive library building, with neither the dreary institutionality of the NAI New Building nor the high-class staidness of NMML.

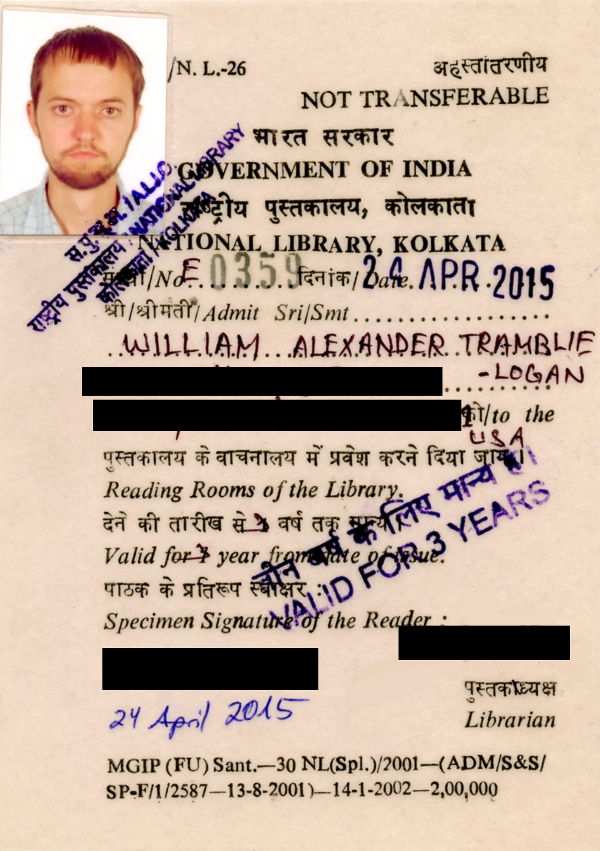

Registering to use the National Library is free, and foreign nationals need only to fill out some forms and hand over one’s passport for copying along with two passport-sized photos. There is no need to present a letter of recommendation or any other credentials. Getting permission to use a laptop computer in the library requires filling out an additional form.

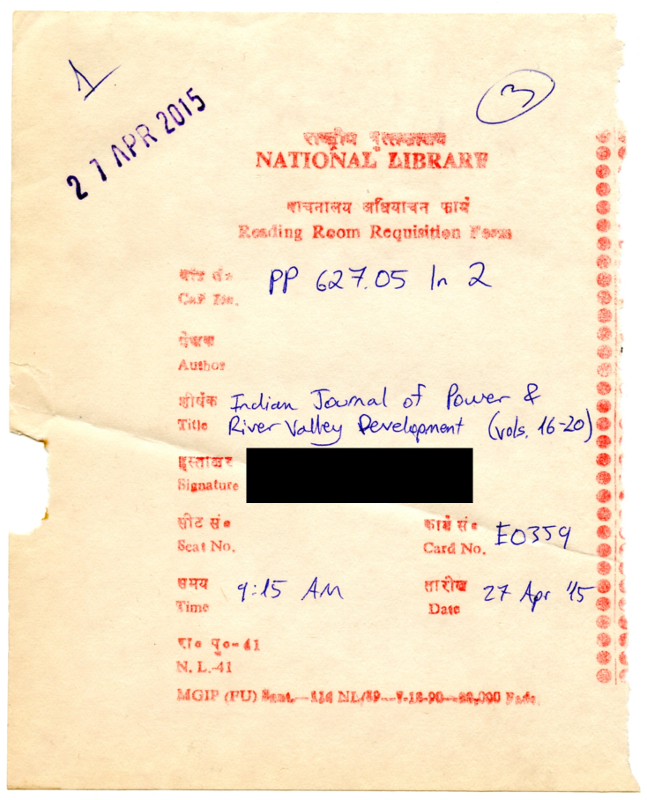

I spent most of my time at NLI in the periodicals reading room in Bhasha Bhawan. The library has a huge collection of magazines and journals bound into volumes, as well as the exhaustive gazettes produced by the central and state governments.

Bhasha Bhawan is climate-controlled, but at some time in the past the periodicals I looked at had been stored in a less favorable environment. Some of the volumes were covered with black dust, and many of them had holes in the pages where bugs or worms had eaten through them.

I also spent some time in the government publications reading room in the Annexe Building. The Annexe is a forbidding early-independence period highrise, with a plaque at the entrance saying that it was dedicated by Nehru in 1961. The government publications reading room is on the second floor, and it is reached by an elevator with doors that are opened and closed by hand. The reading room is as dreary as Bhasha Bhawan is attractive, with bare concrete floors and walls painted in an institutional blue without primer. The shelves holding the government publications are in the reading room, but readers are not supposed to enter the stacks. Instead, readers can request documents by submitting a slip at the front desk.

Since registration and orientation at the National Library were straightforward, I was able to start research quickly and without much confusion. The main challenge I faced at NLI was when employees in certain departments would abscond from work for political reasons. West Bengal has a long history of being ruled by democratically-elected communist governments. Even though the communists have not been the ruling party for several years, they are still active and wield some power. One day, the Left Front (communists) and Bharatiya Janata Party staged a state-wide bandh (strike) to protest the results of the recent state and municipal elections; in the latter, the Trinamool Congress won a huge victory (114 seats for the TMC as opposed to 15 for the communists and seven for the BJP).

Wall-painting by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) announcing a statewide strike on April 30, 2015.

Despite the huge showing for the Trinamool Congress in the election, much of the city went on strike, including some workers at the library. I spent the morning of that day in the periodicals room, and I had no trouble getting the volumes I needed. But when I went over to the government publications reading room in the afternoon, a lone worker there told me that most of the staff were on strike, so I wouldn’t be able to request documents. I left the library early that day, at 2:00.

The next day was May Day, an important holiday in India’s most communist city. The staff at the library departments were back at work, but then in the evening my bus got trapped in an epic traffic jam caused by a long parade of the different trade unions on Chowringhee street.