California state flag. (Source: http://www.library.ca.gov/california-history/state-symbols/, public domain.)

SONOMA, California, USA – The state flag of California, which flies over public buildings, schools, and some businesses and private homes—and not to mention baseball caps, t-shirts, and a huge variety of tourist kitsch—is a white banner featuring a grizzly bear on all fours, a red star, a red band, and the words “CALIFORNIA REPUBLIC.” California is a state, not an independent republic, so why does it say that?

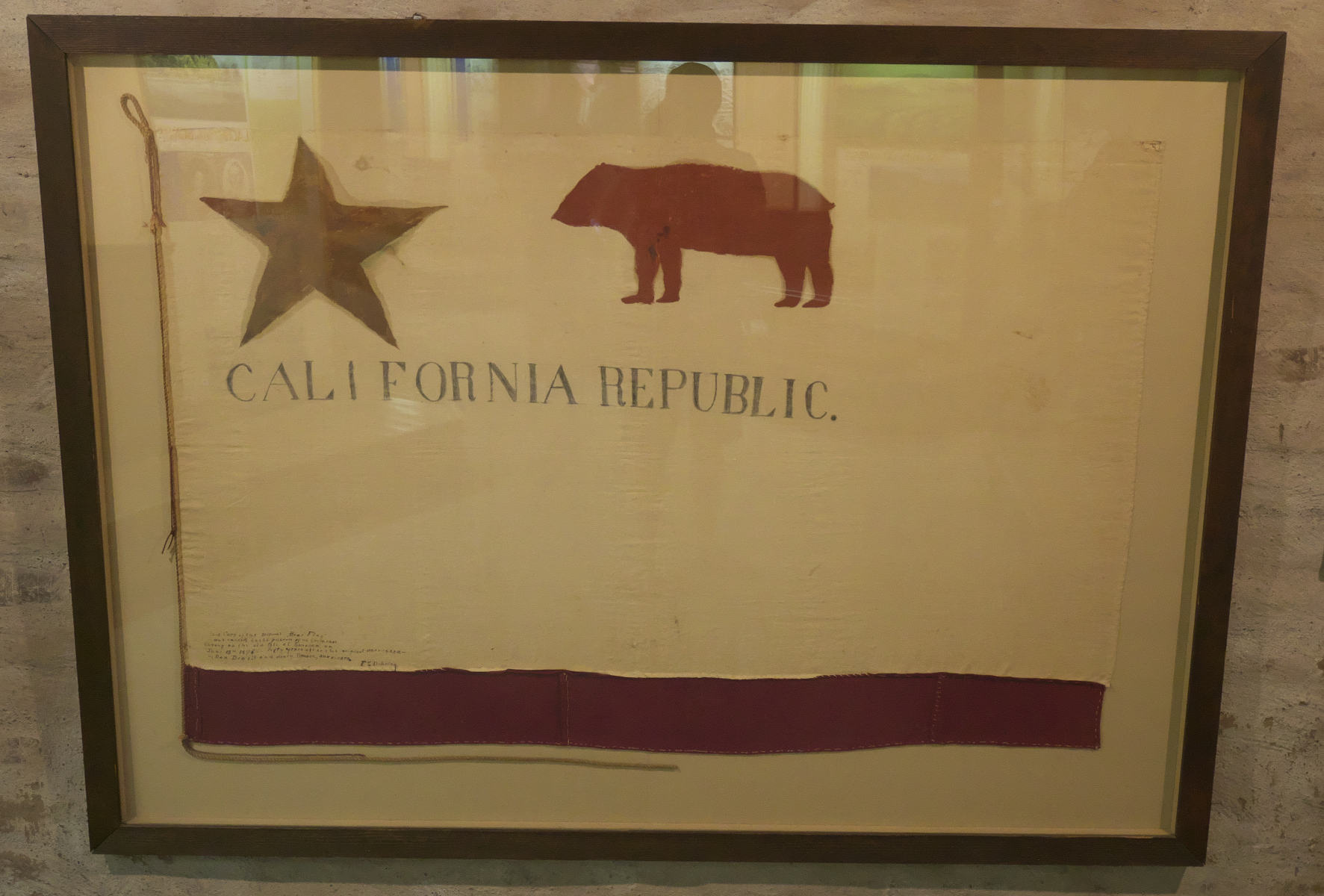

California is indeed not an independent republic, and never really was, but in June 1846, rebellious Anglo-American settlers in Sonoma kidnapped the local Mexican official, General Vallejo, and raised the original Bear Flag in front of the barracks of this Mexican territorial outpost. The next month, the Bear Flag would be replaced by the Stars and Stripes, and the US annexation of Alta (Upper) California would be made official with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. California became a state just two years later, and the state flag design was adopted in 1911, using elements of the original Bear Flag but arranging them much more attractively. (It was remarked at the time that the original “bear” actually looked like a pig).

Replica of the original Bear Flag in the Sonoma Barracks. (The original flag was, like so much else, destroyed in the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906.)

This Sunday, Sonoma held its annual Bear Flag Celebration, timed to be near the anniversary of the raising in 1846. I headed over to investigate, as I have been wondering how the Bear Flag Revolt is commemorated in twenty-first-century California. It was a land-grab by Anglo settlers who thought they deserved to control California more than any Mexicans, but looking at it this way, it would be difficult to celebrate the event in a county and state with a significant Hispanic minority (27% for Sonoma County and 39% for California as a whole). So how is the revolt remembered?

The museum at the Sonoma Barracks hasn’t been of much help in my attempt to understand memory of the Bear Flag Revolt. The barracks were restored by the state of California in 1976-1980, and the museum displays appear not to have been updated since then. The introductory panel presents “Manifest Destiny” as a fact rather than a contested idea.

Having made several visits to the historic buildings in Sonoma, without gaining any insight into memory of the revolt, I thought I might have better luck at the Bear Flag Ceremony that kicked off the day’s festivities on Sunday.

The ceremony was held in front of the vaguely socialist-realist Bear Flag Monument on the Sonoma Plaza opposite the barracks. Native Sons of the Golden West, a fraternal service organization founded in 1875, organized the event. (This is native as in “native-born,” not “Native American.” Judging from the event on Sunday, the membership of the organization seems to be largely but not exclusively Anglo.)

At first, the ceremony didn’t offer me much insight. There were a few reference to the “heroes” of the Bear Flag Revolt, without any explanation about what made them heroic. And there was plenty of generic patriotism (recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and singing of the “Star-spangled Banner”).

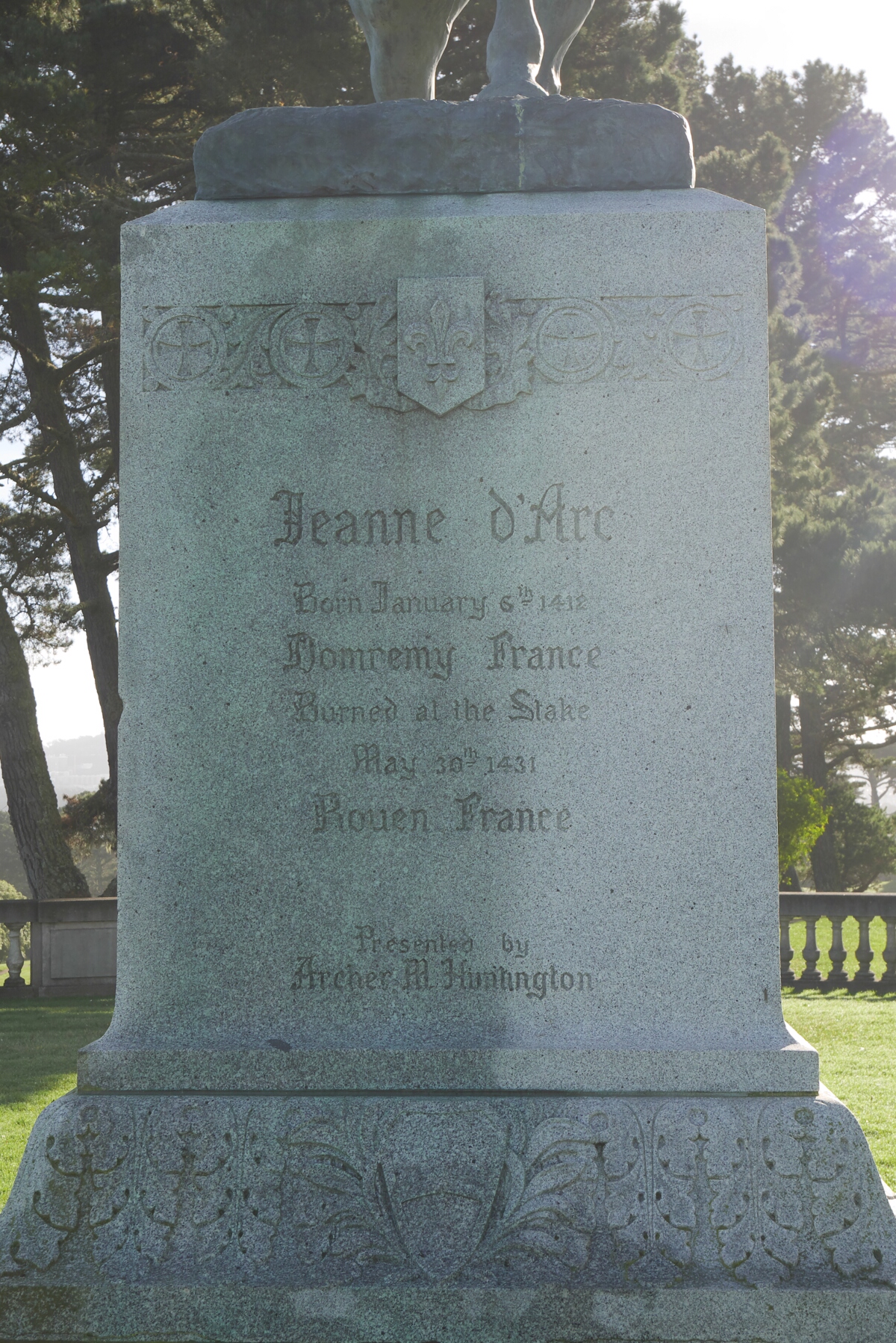

A lineup of historic flags in at the Bear Flag Ceremony. States of the United States that were once ruled by either Mexico or France really like to commemorate this fact.

Things really got interesting with a speech by Dave Allen, Past Grand President of the NSGW and Chairman of the Historical Preservation Foundation. He explained how interpretations of historical facts can and often do change. “A situation that was generally accepted as fact can be reinterpreted by later historians as having an entirely different conclusion,” he said. As an example, he explained that the snow encountered by the Donner Party in 1846-47 was long presumed to be 22 feet deep, and for this reason the Pioneer Monument in Truckee has a base 22 feet high. But more recent research has shown that the snow was in fact 13 feet deep. PGP Allen spoke only about details like this, but I got the impression that he meant that broader interpretations could be changed as well—such as whether the participants in the Bear Flag Revolt were heroes or not.

Later in the program, Sonoma Mayor Amy Harrington remarked that the Bear Flag Revolt proves that a small group of people can make a big difference. (I suppose it helps if said people have the support of an imperialistic power nearby.) The NSGW gave Mayor Harrington a new state flag, which a color guard raised up a flagpole marking the approximate location where the original Bear Flag was flown. As the new flag was nearing the top of the flagpole, somebody behind me in the audience shouted, “Hip hip hooray!” and others nearby chuckled.

Lowering last year’s state flag on an overly-literal telephone pole that is supposed to mark the site of the original Bear Flag’s raising.

The ceremony concluded with a group singing of the state song, “I Love You California.” Although the words were printed on the back of the program, most people in the audience (your blogger included) didn’t know the tune and couldn’t sing along.

Later in the day, a planned reenactment of the Bear Flag Revolt failed to materialize, so I headed home. Although I would have liked to have seen a reenactment, I had gotten plenty of insight already. I had wondered if the interpretation and memory of the Bear Flag Revolt was constrained by the state or the Native Sons of the Golden West—as, for example, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas guards the historical interpretation of the Alamo. But it seems that this is not the case. NSGW Past Grand President Dave Allen is right: interpretation of the past can and does change. I find it heartening to know that the state of California and the Native Sons of the Golden West are open to new interpretations.