Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas is synonymous with NASA’s human spaceflight program for much of the general public—especially those of us who grew up watching Apollo 13. In 2003, back when I was a high schooler, I visited Johnson Space Center for a nerdy spring break. Twenty years later, I revisited my memories and video footage from that trip to make the video embedded above about the history of JSC and what I saw when I visited.

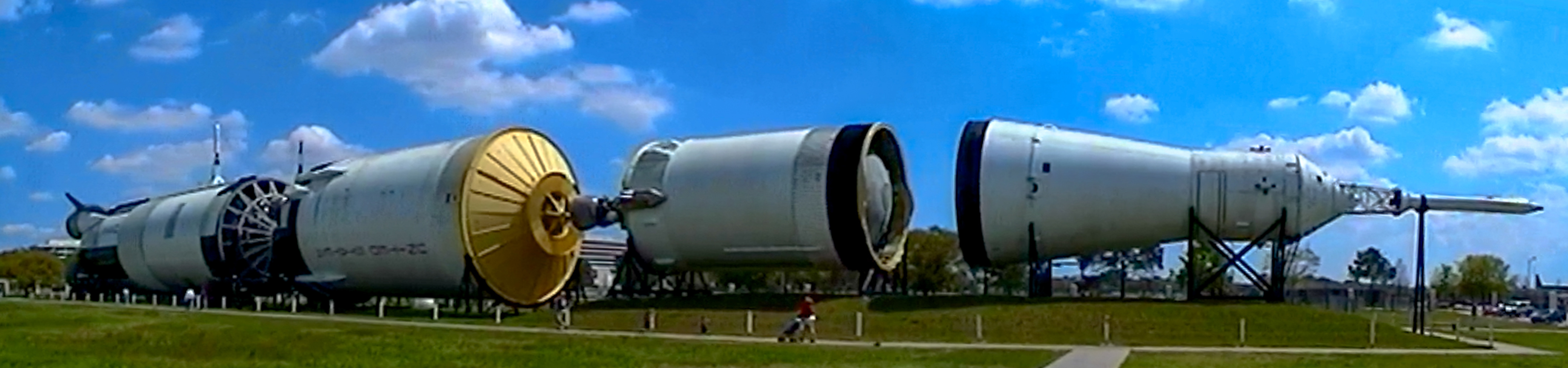

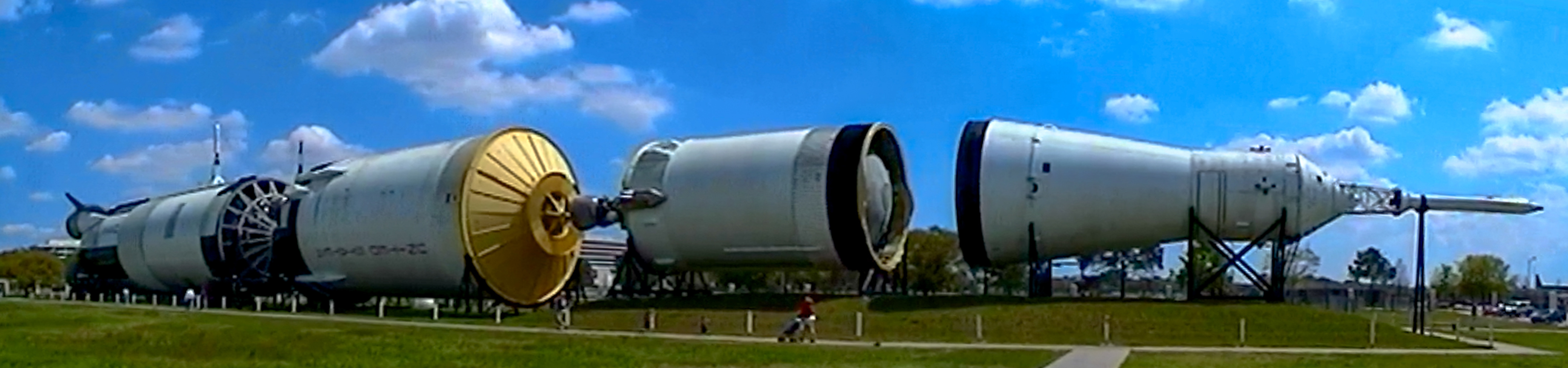

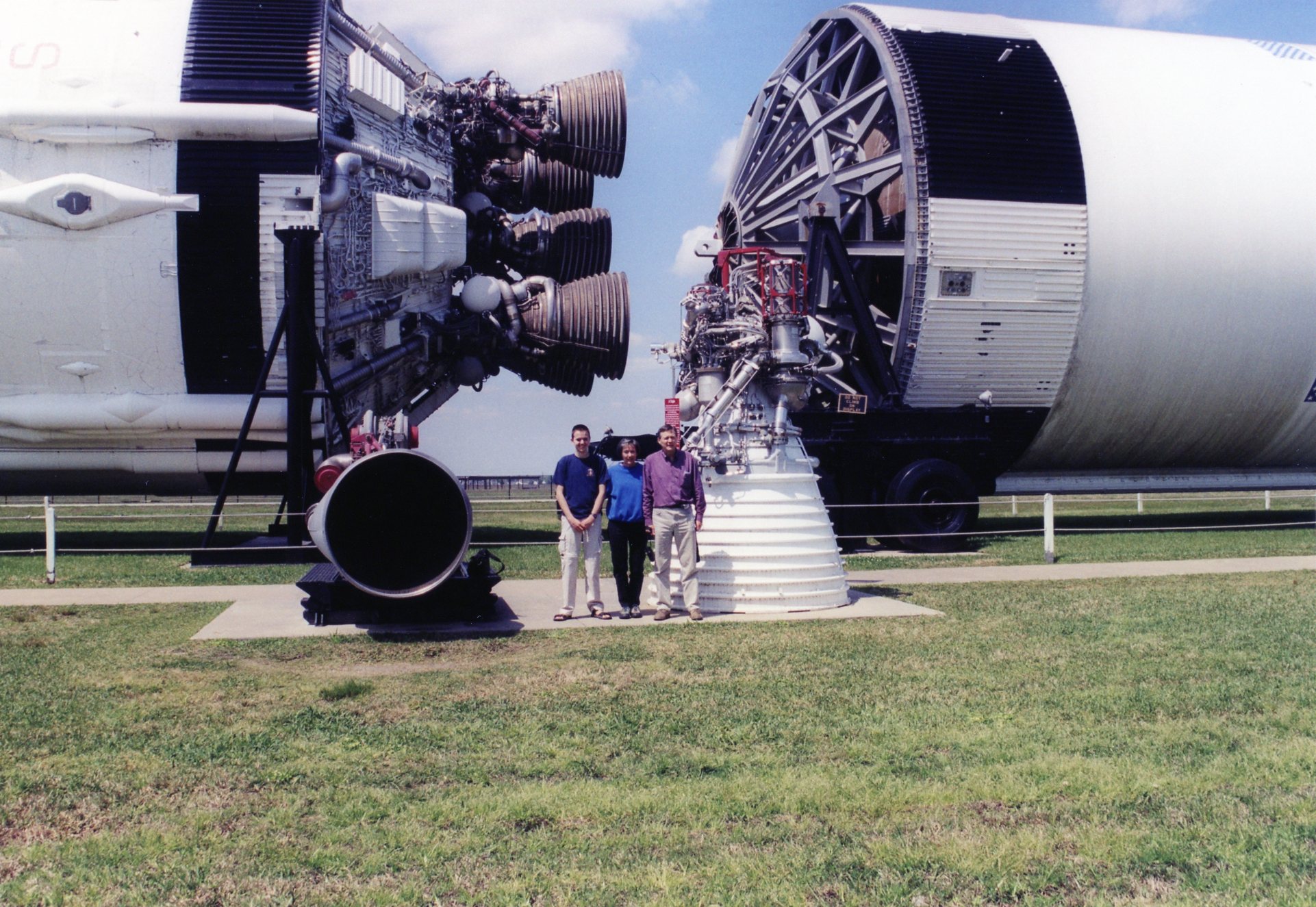

Photos from my 2003 visit to Johnson Space Center: Your blogger and his parents posing between the S-IC and S-II stages of the Saturn V rocket on display.

In writing the script for this video, I relied heavily on Suddenly, Tomorrow Came…: A History of the Johnson Space Center, by Henry C. Dethloff [PDF]. It is a NASA History book, and as usual for books in that series, it is academic and well-researched, but also well-written. Other NASA History books I referred to included The Space Shuttle Decision, by T.A. Heppenheimer [PDF]; and Stages to Saturn, by Roger Bilstein [PDF, print].

For a video of this length, in which only a portion of it consists of footage that I shot, it was a real challenge to find archival footage or stills to match the narration. The NASA Image and Video Library was useful, and I always looked there first. Its holdings are limited, though, especially for material older than 10 or 15 years. The best source for archival footage of the Apollo program in particular was the National Archives and Records Administration, which has quite a lot of digitized footage, much of which is in HD. NARA was less useful for the Space Shuttle. I also found Internet Archive to be indispensable, because it has plenty of high-res stills and mostly low-res videos about the Space Shuttle, which I couldn’t find anywhere else even though they were created by NASA.

Back in 2003, consumer-grade HD video cameras were not widely available. Camcorders recorded video on tapes in SD (480p), either in analog format or digitally. I used a Sony DCR-TRV340 camcorder, which recorded digital video in D8 format on tapes that were backward-compatible with the analog Hi8 tapes that our previous camcorder had used. The camera had an IEEE 1394 Firewire port, which allowed a computer to capture video from the tapes in lossless digital format. Since I no longer have a computer with a Firewire card, I used a ClearClick Video2Digital Converter to transfer footage to my computer for this video. The quality of the transfer probably wasn’t perfect, but it was definitely good enough.

Overall, my video footage from 2003 was of disappointing quality. The cuts and camera movements were fast, and the colors were ugly. I couldn’t do much about the camerawork, but I could adjust the exposure and colors in Premiere, vastly improving the appearance of the picture. I’ll make it a point to do these adjustments whenever I use my old video footage in the future.

Sources for the video

Bilstein, Roger E. Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles. 1980; repr. Washington, DC: NASA History Office, 1996.

Dethloff, Henry C. Suddenly, Tomorrow Came…: A History of the Johnson Space Center. N.p. [Houston, TX]: Johnson Space Center, 1993.

Heppenheimer, T.A. The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA’s Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle. Washington, DC: NASA History Office, 1999.

Olasky, Charles. “Shuttle Mission Simulator.” NASA conference publication, 11th Space Simulation Conference, 1980. NTRS, 19810005636.