As I described in my previous post, Alabama has some old and impressive dams. Although I lived within easy driving distance of several of them in graduate school, I knew nothing about them for the first two years that I lived in Alabama. My discovery of these dams at the end of my second year of grad school was a revelation. It changed how I viewed Alabama. It also sparked an enduring interest in dams that influenced my dissertation topic and subsequent research.

After my first encounter with the dams of Alabama, I made it a point to visit as many dams as I could in my remaining two and a half years living in the state. Here is a gallery of my pictures of the dams that I saw, organized by river system.

Tallapoosa and Coosa Rivers

The Tallapoosa and Coosa are two rivers in the Piedmont of east-central Alabama. The rivers exit the Piedmont and flow into the flatlands of the Black Belt before joining together near Wetumpka and becoming the Alabama River, which drains into the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile Bay.

Alabama Power, a private electric utility, built dams on the Tallapoosa and Coosa in the early 20th century. I was able to see all of those dams, as well as some newer ones. There are also Army Corps of Engineers lock-and-dams downstream on the Alabama River, but I never got to see any of them.

Starting with the Coosa River, which is the western of the two. This is Lay Dam, Alabama Power’s first dam in the Alabama Piedmont. It entered service in 1914. Originally named Lock 12 Dam, it was renamed in honor of the founder of Alabama Power in 1929.

Jordan Dam (1928), the last dam on the Coosa River. It is located at the Fall Line, where the Coosa reaches the flatlands of the Black Belt. This is the most impressive of the Alabama Power dams, in my opinion.

The biggest dam on the Tallapoosa is Martin Dam (1926), which impounds the attractive Lake Martin. It is tucked away in a ravine and hard to get a good picture of.

Downstream from the Tallapoosa is the smallest dam on the Tallapoosa, Yates Dam. Completed in 1928, it was built on the site of Alabama’s first hydroelectric plant, which was built in 1912. This is a telephoto view from the next dam downstream, Thurlow Dam.

Thurlow Dam (1930), at Tallassee on the Fall Line. It is the easiest to see of any of these dams, because a bridge runs right in front of it.

I was able to see two newer dams on the Tallapoosa–Coosa river system. This one is Logan Martin Dam, upstream of Lay Dam on the Coosa. It is named after William Logan Martin (a truly auspicious name!), an attorney-general of Alabama. A road runs across its crest.

The most unusual dam on Tallapoosa–Coosa is Bouldin Dam (1967). What makes it unusual is that it is built on an artificial canal connected to the Coosa River, rather than the river itself. Although the dam itself is not especially impressive, it has the largest powerhouse of any of the dams on the Tallapoosa–Coosa (225 MW).

Black Warrior River system

On the western side of the state, Alabama Power has three dams on the Black Warrior River system: Smith Dam, Bankhead Dam, and Holt Dam. Once, on the way back from a camping trip in Bankhead National Forest, I tried visiting all three dams, but I was only able to visit Smith Dam. I made it as far as the locked gate for Bankhead Dam, and I missed the turn for Holt Dam entirely and just drove through Tuscaloosa and headed home.

Smith Dam (1961) is located on the Sipsey River, a tributary of the Black Warrior. At 300 feet high, it is the tallest dam in Alabama. It is a postwar rockfill dam and has a fairly cyclopean appearance.

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River makes a giant bend through northern Alabama, and it is dammed three times during its course through the state. I was able to visit two of the dams (Wheeler and Wilson), but I was never able to make it to the third (Guntersville). All three of the dams are owned and operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority, a public utility established in 1933 during the New Deal.

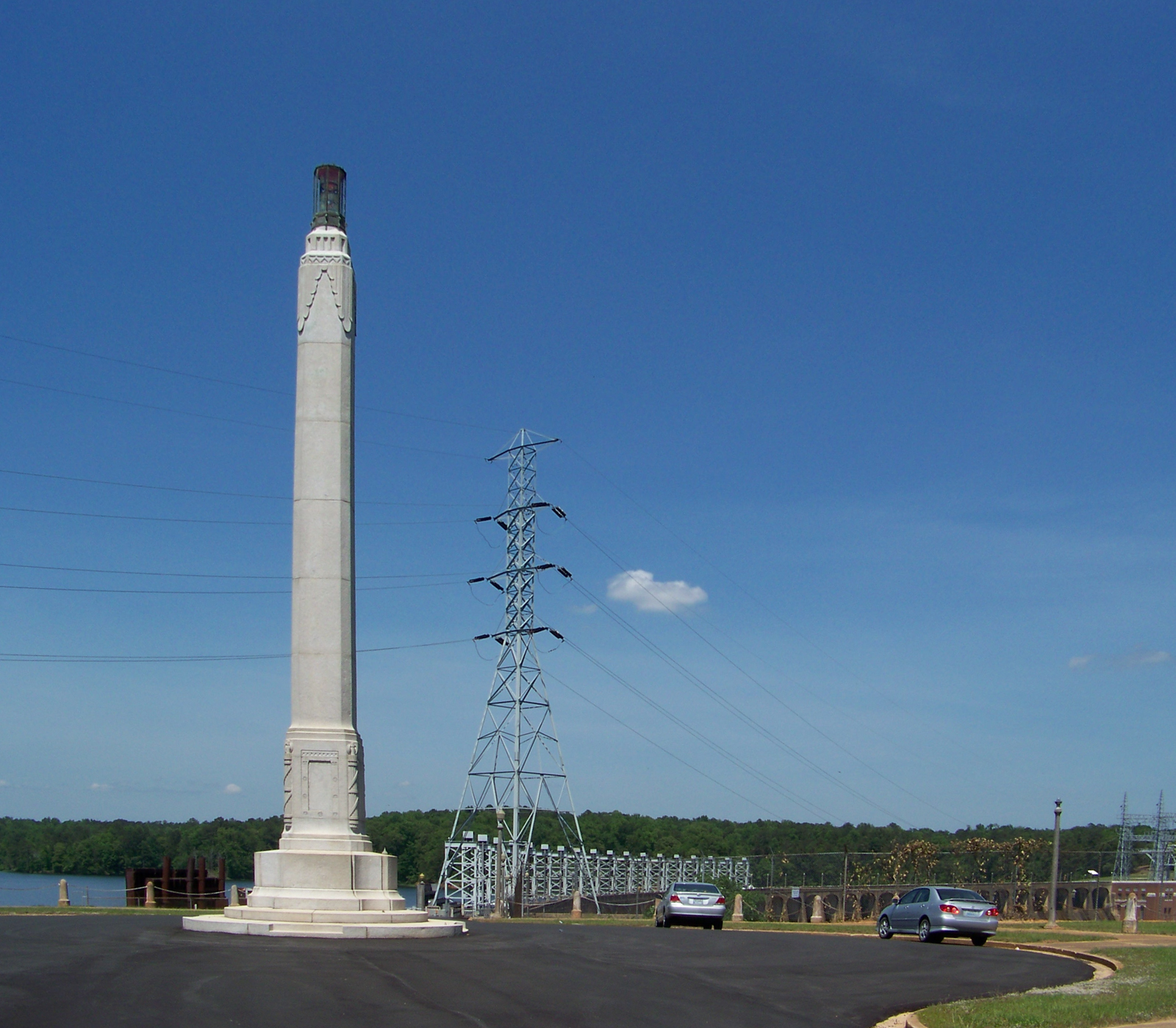

Wilson Dam, between Muscle Shoals and Florence in northwestern Alabama, is the oldest of the three TVA dams in the state. Built in World War I to power a munitions factory, it became part of the TVA when the utility was established by act of Congress. Wheeler Dam, not far upstream, was completed in 1936. Both dams are much larger than the Alabama Power dams to the south. Wheeler Dam is over a mile long and has a powerhouse with a generative capacity of 402 MW.

Detail of the spillways on Wheeler Dam (more modern and less elegant than the Wilson Dam spillways).

An antique crane on display on the southern side of Wheeler Dam. (It made me think of the children’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel.)